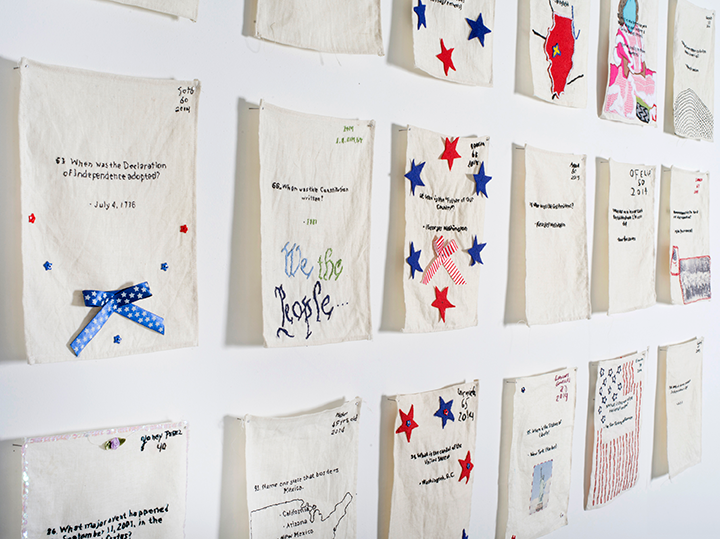

Collection of Samplers: Individual Questions and Answers Sewn by Non-US Citizens Living and Working in the US (Oakland, San Francisco, San Diego, Modesto, Manteca, Millersville, Chicago), 24 out of 80 samplers

Aram Han Sifuentes2013 - 2015 Cotton thread and fabric on linen 53 in. x 66 in. x 1 in. Courtesy of the artist Photo credit: Hyounsang Yoo

contributor

XAram Han Sifuentes

- See All Works

- visit website

- [email removed]

Aram Han Sifuentes is a fiber, social practice, and performance artist who works to claim spaces for immigrant and disenfranchised communities. Her work often revolves around skill sharing, specifically sewing techniques, to create multiethnic and intergenerational sewing circles, which become a place for empowerment, subversion and protest. Her work has been exhibited at the Pulitzer Arts Foundation (St. Louis, MO), Jane Addams Hull-House Museum (Chicago, IL), Hyde Park Art Center (Chicago, IL), Chicago Cultural Center (Chicago, IL), Asian Arts Initiative (Philadelphia, PA), Chung Young Yang Embroidery Museum (Seoul, South Korea), and the Design Museum (London, UK).

Aram is a 2016 Smithsonian Artist Research Fellow, 2016 3Arts Awardee, and 2017 Sustainable Arts Foundation Awardee. She earned her BA in Art and Latin American Studies from the University of California, Berkeley, and her MFA in Fiber and Material Studies from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. She is currently an Adjunct Associate Professor at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

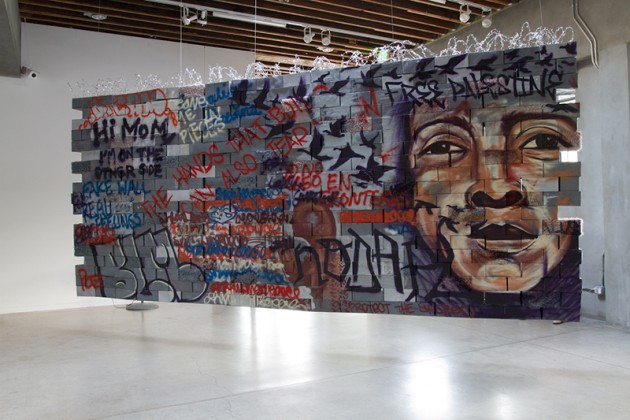

Sewing is a time-based practice. Fiber as a medium speaks a language of accessibility, intimacy, and time. From its inception, it has been touched. To sew, the hand, armed with a needle, pierces the cloth, pulls the needle up, pierces the cloth, and pulls the needle down. Each sewn thread creates an indexical line of invested time, gesture, and rhythm. As an artist I use this needle and thread to mine from my experiences as an immigrant to address issues of labor and identity politics. I try to unpack these complex labor and immigrant histories by engaging with people through long term projects utilizing varied social practices. At the root, is a research-based practice revolved around collecting materials: oral histories, data, commissioned artifacts, handmade objects, and remnants of handwork. I then invest in the materials with my own hands with time and labor in order to create large-scale installations and meticulously labor intensive works. However, being about invisible and Sisyphean labor, my works rarely suggest finality. The needle is a political tool. It pierces and binds membranes together. The thread that it steers is tied off and remains while the needle continues to bind and mend. In my art practice, I use that needle to stitch together various histories and discourses revolving around the simple act of sewing. However, this act is anything but uncomplicated. The creation of each stitch engages sewing’s complex histories and politics of traditional, industrial, feminist, immigrant, and artist labor.

location

X- Born: Seoul, South Korea

- Based: Chicago, IL, USA

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_Cropped.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

-72dpi.jpg)

-72dpi.jpg)

comments

X