1.1 EVEN GOT CULLUD POLICEMANS

I’m gonna do like a Chinaman… go and get some hop Get myself a gun… and shoot myself a cop—Mamie Smith, “The Crazy Blues” (Perry Bradford, composer) Of all the wonders that Jazz Age Harlem has to offer to a wideeyed...

Established in 2013 with the launch of the Center for Art and Thought (CA+T), the Artist-in-Residence Virtual Residency is a one of a kind program that moves from the delimited physical spaces of a center or institution to the virtual spaces of the Internet. This de-centering of the physical allows the resident to work from anywhere in the world, provided that s/he has a connection to the Internet.

Over the course of his/her residency, the artist has the opportunity to work towards the completion of a project, such as a manuscript, a collection of stories, or scholarly article. The fundamental goal of the residency program is to facilitate the artist’s critical engagement with the public through his/her contributions on a virtual platform. This platform is a space for the artist to garner inspiration from an engaged audience and to work through ideas, both visually and textually.

At the end of the residency, the artist will present his or her work online. For example, s/he might present a digitally recorded podcast, a live online streamed talk, or curated online exhibition. For more information about the Artist-in-Residence Virtual Residency, please e-mail your inquiry to residency@centerforartandthought.org.

I’m gonna do like a Chinaman… go and get some hop Get myself a gun… and shoot myself a cop—Mamie Smith, “The Crazy Blues” (Perry Bradford, composer) Of all the wonders that Jazz Age Harlem has to offer to a wideeyed...

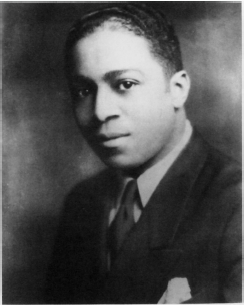

The second installment in a three-part sequence on “City of Refuge,” a 1925 short story by Rudolph Fisher. You can start here, or scroll back for earlier posts if you’d like. At the end of “City of Refuge,” the Rudolph Fisher short story I...

The conclusion to a three-part sequence on “City of Refuge,” a 1925 short story by Rudolph Fisher. For earlier posts, please scroll down. Earlier in this sequence of posts on Rudolph Fisher’s 1925 short story, “City of Refuge,” I discussed...

This is the first installment in a sequence on the geography of the lost Afro-Asian century. Scroll down for older posts, and come back for another installment next week. Back to the land of California To my sweet home...

This is the second post in a sequence on the geography of the lost Afro-Asian century. Scroll down for older posts, and come back for another installment next week. Years later, I made it back home to California. Happy birthday...

The third installment in a sequence on the geography of the lost Afro-Asian century. For earlier posts, please scroll down.The Afro-Asian century begins with a prophecy. The lost Afro-Asian century begins with a...

Part four in a continuing sequence on the geography of the lost Afro-Asian century. For earlier posts, scroll down. When you live in a falling empire, reading the news is doubly uncanny—like déjà vu, combined with the unsettling premonition...

The final installment in a sequence on the geography of the lost Afro-Asian century. Scroll down for earlier posts. I am looking for a map to everything that comes after the ending. worlds within worlds, each one lost image from...

The regularly scheduled next installment in a three-part sequence on “City of Refuge,” a 1925 short story by Rudolph Fisher, comes tomorrow. Scroll back if you missed the first one; stay tuned for more. Meanwhile, an unanticipated...

Introduction to an ongoing series published every Sunday or so.1.All investigators experience a driving urgency to uncover evidence of some sort, useful to make a particular claim. I’ve always wanted to know why, in my experience, Filipinos and...

I’m gonna do like a Chinaman… go and get some hop

Get myself a gun… and shoot myself a cop

—Mamie Smith, “The Crazy Blues”

(Perry Bradford, composer)

Of all the wonders that Jazz Age Harlem has to offer to a wide-eyed migrant from North Carolina just out of the subway at 135th Street—

“unnumbered tons of automobiles and trucks and wagons and pushcarts and streetcars”;

the promise of money, of “rights that could not be denied you” and of “privileges, protected by law”

One is “a pair of bright green stockings,” whose impossible color

—“loud green!”—

is itself enough to hold your strong man in their thrall.

More astonishing still is the existence of “cullud policemans,” attested by that “handsome brass-buttoned giant,” whose sharp whistle and outstretched, white-gloved hand

—see, there!—

carries the authority to stop vehicles loaded with white passengers in their place.

“Done died an’ woke up in Heaven,” thinks the magnificently named King Solomon Gillis, the protagonist of Rudolph Fisher’s classic New Negro Renaissance story, “City of Refuge.”

* * *

"His death was attributed to his own X-ray machines."

* * *

Your man, King Solomon Gillis—the story relishes each opportunity to repeat his full name—is of course named ironically, for he is by all evidence a fool, everyone’s and anyone’s fool, from the moment he climbs out of the subway until his confrontation by one of those “cullud policemans” at the story’s end. There is something recursive in the joke the story makes of his name, something dizzyingly ungrounded that laughter both dispels and leaves to squirm—something like making fun of Raven-Symoné for making fun of black people’s names.

Forget that for now, but know this character is yours, your own heroic fool, whose misadventures are offered up for your pleasure, entertainment, and edification in a manner that, it is implied, is inaccessible to the man himself. He is an open book that can be read by everyone in Harlem not named King Solomon Gillis.

The plot of his story is simple enough; if you’ve ever heard the skit in the middle of Stevie Wonder’s “Living for the City,” you know it already.[1] Arriving in Harlem on the run from a likely lynching in North Carolina, King Solomon Gillis is immediately marked by one Mouse Uggam, a smalltime criminal and World War I veteran who just happens to be his homeboy from back in Waxhaw, and who pretends to take him under his wing. King Solomon has only two desires—to become a policeman himself

(“so I kin police all the white folks right plumb in jail!”)

and to get a woman like the one with the green stockings. But soon enough, he’s innocently distributing Mouse’s special “French medicine” from behind the counter of his job at a grocery owned by an Italian immigrant. Before he knows it, he’s being arrested in Mouse’s boss’s cabaret by two white police detectives who’d been on the trail of their drug trade.

In the end, the story grants him this—

“the tall Negro could fight.”

Spotting the green-stockinged woman, who has somehow ended up in the same nightclub, he distractedly tosses the white men aside like soft dolls as fragmented memories of the treachery he’d fled stutter towards his consciousness:

“White—both white. Five of Mose Joplin’s horses. Poisoning

a well; A year’s crops. Green stockings—white—white—”

And then the black officer arrives.

* * *

Because the story is so elegantly made, it seems churlish to ask whether King Solomon’s apparent naïveté when confronted by the black officer is plausible. The answer is, of course, not really.

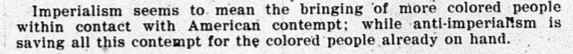

Adam Gussow concedes as much in his essay “‘Shoot Myself a Cop,’”[2] a diligent recuperation of Mamie Smith’s “Crazy Blues” (1920)—the first phonograph record by a black woman, the first blues recording by a black vocalist, and a wildfire hit among Northern and Southern black audiences, credited with establishing the market for what would be known as “race records.” Challenging a longstanding tradition among blues historians of dismissing the number as historically significant but artistically lacking—as an inauthentic novelty barely passing as the blues—Gussow takes an unusual tack, focusing on the largely overlooked couplet cited in my epigraph above. Beginning from the evidence of the record’s commercial success, he asks, “What were these black consumers thinking when they heard poor Mamie fantasize, after losing her man, of shooting a cop?”[3]

The question is not meant to be all that difficult, all caveats about generalization aside. Indeed, Gussow mentions the hapless Gillis himself, with a wink, as the exception proving the general rule of the violent communal antagonism between black people and the police arrayed against them. It was true in 1920 Harlem, where “a tiny minority” of black officers bound to protect their white brethren struggled to contain the righteous “civic fury” of its black residents.

And it was self-evident in the South, where black policemen, like other vestiges of post-Civil War Reconstruction, had long been wiped out by the same forces that made widespread public lynching effectively continuous with the operations of law enforcement.[4]

How, then, could it be possible for a figure like Gillis to be so naïve—someone whose very passage to Harlem is as a fugitive from lynch law, who relates a catalogue of white violence against any minimally successful black farmer to Mouse while simultaneously insisting that his killing of a white man was just an accident?

* * *

“Know whut dey done?

Dey killed

’fo he lef’.

five

glass

o’ Mose Joplin’s hawses

Put groun’

in de feed-trough.

Sam Cheevers

come up on three of ’em one night

pizenin’ his well.

Bleesom

out o’

he better git

to leavin’

beat

sixty

Soon

Crinshaw

acres o’ lan’

an’ a year’s crops.

’s a nigger make

a li’l sump’n

An’ ’fo long

Dass jess how ’t is.

ev’ybody’s

goin’ be lef’!”

* * *

What if King Solomon Gillis is not such a fool, after all?

To uphold this alternative is to read the story against the grain, perhaps, but in a way that is made possible by the story’s own artistry. For what makes him so persuasive and appealing, as a fool, is his utter conviction and sheer opacity: a character can only be so impossibly unknowing if he carries himself like the bearer of a secret no one knows, like an open book no one knows how to read.

In the same way, the ending of the story is more powerful by withholding the certainty of closure. Facing the black officer, Gillis is at first bewildered:

Into his mind swept his own words, like a forgotten song suddenly recalled:—

“Cullud policemans!”

The officer stood ready, awaiting his rush.

“Even—got—cullud—policemans—”

Very slowly King Solomon’s arms relaxed; very slowly he stood erect; and the grin that came over his features had something exultant about it.

This is the end; what happens next, the story will not say.

Readers have typically assumed that he has begun to surrender, his muscles relaxing in submission as his face twists in delightful anticipation of a justice that will not come. Yet because this interpretation pushes the joke of King Solomon’s foolishness from comedy to the precipice of horror—that grin, as uncanny as that on an old racist doll!—it must be left to hang.

And so this interpretation is not denied, but actually shored up by the story’s refusal to explicitly foreclose its opposite—that Gillis now fully understands the meaning of “cullud policemans,” that his body is preparing for an exercise of violence beyond anything the story has yet shown.

In other words, the ending must be structurally indeterminate because neither the likeliest interpretation nor the slim alternative would be as effective if they were actually depicted. Either way, if the story told you what happened next, it would suddenly be less plausible and satisfying.

Fool or not, Gillis’s understanding of the function of policing may be more insightful than it appears. For you or me, living through the early phases of a resurgent movement against the systematic police violence delimiting the lives of black people, the blues song’s offhand fantasy of cop-killing might seem less crazy than King Solomon’s wild enthusiasm for “cullud policemans”—but the insight they express is, in truth, the same.

When he imagines becoming an officer in order to police all the white folks right plumb in jail, he is properly apprehending and reversing the racialized and racializing logic of policing as a mode of control. (Change “white” to “black,” and you have the revenue policies for North St. Louis County.) Like the song, King Solomon denies—he does not even entertain—the illusion that the police are defined by an inclusive principle of justice, rather than by the exercise of a violence that establishes a community over against its internal enemies.

And if he fails, in his initial excitement, to appreciate the capacity of white supremacy to incorporate and assimilate nonwhite agents, his desire to seize the apparatus of state-sanctioned violence draws on a revolutionary precedent that, in 1925, is within living memory.

In a recent set of lectures, “Mike Brown’s Body,” the historian Robin Kelley notes that, as part of the continual armed struggle that was the aftermath of the Civil War, black organizers in the rural South formed militias and struggled for control over the local offices of the criminal justice system (about 46:30 in). Reconstruction’s eventual defeat may have spurred the mass migration of black Southerners to places like Harlem, but it did not change their fundamental relationship to US policing, nor did it erase the everyday knowledge that is shared as a community living in the truth of justice.

And so it is not to dismiss, but to commend King Solomon’s wisdom that you might ask, What does he know of justice? All he knows is violence.

* * *

#BlackLivesMatter, and the specificity of this slogan, rather than some false universality,[5] turns out to be, among other things, the entry point to understanding the forgotten histories of other racialized groups. The hopheaded murderous Chinaman that Mamie Smith longs to emulate is just one example, hiding in plain sight. Start looking, and you’ll find that US culture, especially prior to the Cold War, is littered with stereotypes of Asians with a predilection for antiwhite violence deemed greater and more volatile than that of black people.

But in the next installment, I’ll follow the path of King Solomon’s story to other, unexpected histories. Tracing it back a quarter-century to the Philippine-American War, and then ahead to the literature of midcentury Filipino migration, I’ll suggest that each is structured by the same relation to white American racial violence.

The question is simple: if King Solomon is not a fool, what knowledge does he bear?

The answer may be found in a song.

Welcome to the City of Refuge! New posts here every Wednesday, through the end of the year. Read with me, and tell me about it here and here.

[1] It’s been a long time, but I think I borrowed this observation from Joycelyn Moody, who was the first person to read this story with me. Either way, thanks, Joycelyn, for teaching me what it means to become a reader.

[2] Adam Gussow, “‘Shoot Myself a Cop’: Mamie Smith’s ‘Crazy Blues’ as Social Text,” Callaloo 25.1 (2002): 8-44, and reprinted in his Seems Like Murder Here: Southern Violence and the Blues Tradition, Chicago: U of Chicago Press, 2002. But if you read that, you also need to read Daphne Brooks’s take, “A New Voice of the Blues,” in Greil Marcus and Werner Sollors’s New Literary History of America, Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2009: 545-50.

[3] Gussow 13.

[4] Gussow 13-15.

[5] The alternate, “All Lives Matter,” is entirely typical of the dominant concept of universality in U.S. history, which aspires to a delusion of whiteness by explicitly repudiating blackness: “all” is what you are left with when you make “black” disappear.

The second installment in a three-part sequence on “City of Refuge,” a 1925 short story by Rudolph Fisher. You can start here, or scroll back for earlier posts if you’d like.

At the end of “City of Refuge,” the Rudolph Fisher short story I began discussing in my last post, the protagonist King Solomon Gillis—a North Carolina fugitive in 1920s New York—finds himself about to be arrested by a black police officer. Momentarily dumbfounded, his mind lurches into awareness remembering the sight that amazed him when he first arrived in Harlem, days earlier.

“Cullud policemans!”

—the words appear in his mind

“like a forgotten song suddenly recalled”

—and, if any real insight is possible for this character, it emerges here.

King Solomon, as I explained earlier, is the story’s perfect fool—it’s as if everyone else in the story, along with the narrator and the reader, is in on a joke he doesn’t understand, and so it must also be possible that he gets the joke and all the rest of us are on the outside. In this post, I want to consider what kind of knowledge this figure might bear, if he isn’t such a fool after all. Here, I want to return to an essay I mentioned earlier, by the blues historian Adam Gussow, who seems to think he knows which song King Solomon is trying to remember.

Gussow’s essay, you may recall, aims to rehabilitate a historically pathbreaking but aesthetically derided bestselling 1920 record, “Crazy Blues,” written by Perry Bradford and performed by Mamie Smith. Focusing on an often overlooked couplet he calls the “emotional crescendo” of the last verse—

I’m gonna do like a Chinaman… go and get some hop

Get myself a gun… and shoot myself a cop[1]

—Gussow glimpses the brief resurfacing of a long tradition of “badmen” (and sometimes badwomen) across black folklore, music, and literature. In particular, Gussow is eager to suggest that Perry Bradford had one particular badman in mind—the legendary Robert Charles.

A Mississippi native who’d escaped lynch-ridden Copiah County for New Orleans a few years earlier, Charles was unjustly accosted by three policemen on a neighbor’s doorstep on July 23, 1900. After Charles and an officer exchanged gunshots, he fled, and when the police caught up with him later that night, he killed two before escaping. Extensive white rioting over the next few days claimed three black lives and injured dozens more. But before Charles was finally killed, the building he was hiding in set aflame, he managed singlehandedly to shoot over two dozen whites, killing seven, including five members of the mob that came to lynch him.

Gussow’s interest in this particular badman stems from his subsequent appearance in a noted episode in blues history, in which the famed New Orleans musician Jelly Roll Morton told the folklorist Alan Lomax about Charles’s legend, but refused to sing the song that was supposed to have circulated about it. By insisting he’d forgotten the song in order to keep out of trouble, Morton ensured that several generations of blues collectors would obsess about recovering the tune. Marshalling what he admits is circumstantial evidence, Gussow does his best to suggest that the reference to cop-killing in “Crazy Blues” was explicitly composed as its echo.

But other reverberations are also possible. Charles, it is reported, was a follower of Bishop Henry McNeal Turner, the prominent African Methodist Episcopal churchman best known today for promoting black emigration to Liberia, who advocated for armed black self-defense. It is also said that Charles was radicalized by the infamous 1899 lynching of Sam Hose in Georgia, a case most thoroughly documented by the great anti-lynching crusader Ida B. Wells-Barnett—another proponent of armed self-defense—who would subsequently publish a record of Charles’s own death. W.E.B. Du Bois himself would later report that it was Hose’s murder, and his own near-encounter with a butcher shop display of Hose’s severed knuckles, that redirected his path from an idealistic social scientist to a committed political activist, guided by “a red ray which could not be ignored.”

This red ray reached as far as the Philippines, via Hong Kong, where exiled leaders maintained global networks for the nationalist side in the ongoing Philippine-American war. Hence, on their first movement outside Manila, African American soldiers of the segregated 24th Infantry discovered propaganda placards left in their path, which announced,

“the blood of your brothers Sam Heose [sic]

and Gray proclaim

vengeance.”[2]

Opposition to the Philippine American war, shared by Du Bois and Wells, was typical of black public opinion at the time, although a line was usually drawn at criticism of black soldiers, who were instead praised as models of the civilized and civilizing capacity of the race.

But Bishop Turner danced on that line:

“I boil over with disgust when I remember that colored men

from this country that I am personally acquainted with are there

fighting to subjugate a people of their own color and bring them

to such a degraded state.

I can scarcely keep from saying that

I hope the Filipinos will

wipe such soldiers

from the face of the earth.”

Indeed, a handful of black soldiers chose to desert and switch sides. The best known was a teenaged corporal of the aforementioned 24th Infantry from Tampa, David Fagen, whose exploits as an officer in Emilio Aguinaldo’s forces became legend. Promoted to captain under Gen. José Alejandrino, and referred to as a general in the U.S. press, he persisted in guerilla warfare even after Aguinaldo and Alejandrino surrendered. The bedeviled US Gen. Frederick Funston’s frustrated desire to lynch him was so well known that his own sister-in-law mocked it at a Christmas dinner, conjuring a vision of Fagen’s hanged body in a playful bit of light verse:

By Jiminy Christmas Fred

What’s this I see?

Poor old Fagen

Hanged to a tree?

How did it happen

This is queer

Tell us about it

We’re dying to hear.

Fagen was supposedly killed in December 1901 by a Filipino hunter named Anastacio Bartolomé, who delivered his severed, decaying head to U.S. forces, along with a few personal effects. But there is good reason to believe this grisly evidence was not entirely credited by the authorities, and regardless, Fagen’s story continued and continues to circulate.

Who was David Fagen, really? Where did he come from, and what happened to him? After decades on his trail, the military historian Frank Schubert finally concluded that the most apt way to understand Fagen’s identity was to recognize him as a figure of legend—the badman.[3]

* * *

text: LA Times, 16 August 1901

photo: LA Times, 17 August 1901

* * *

It was impossible to capture David Fagen, because he had already escaped into myth.

This myth has been rediscovered, decade after decade, among all those captivated by militant resistance to the racist violence of U.S. empire, on both sides of the Pacific, war after war after war. What history drags back from myth, every time, is always as decomposed and dubious and uncanny as that sack of moldering remains

—(oh!)—

hauled back from the field to be presented to the gathering audience.

David Fagen is not here, not any more than Sam Hose or Robert Charles or King Solomon himself. For that, you and I should give a cheer, even if it is uncertain what point of identification you or I might take in rehearsing this story—the suspicious Bartolomé, the distrusting white colonial authorities, or some cold-eyed darker observer keeping her own counsel at the margins of the scene.

Before you can ask what message Fagen brings, you must ask how he could be made to speak. What is left of his story is, after all, only a token, like the head in the sack, the knuckles in the window, or the blood of your brothers that both speaks and acts at once, beyond death, proclaiming vengeance.

Whose voice is this? Aren’t these really someone else’s words, poorly disguised, setting themselves up within violence’s gruesome trophy to promote their own interests? Or is it possible that an agency exists within the inanimate or murdered object, that the dead can find expression through the bodies of the living, their tongues and mouths and fingers? Doesn’t every act of ventriloquism raise the specter of possession?

Welcome to the City of Refuge! Coming up in the conclusion to this sequence: jokes, lies, and the secret identity of a bicycle thief. New posts every Wednesday, through the end of the year. Read with me, and tell me about it—a comment section should appear below if you’re signed in to Facebook, but you can always reach me here and here.

[1] Gussow 10.

[2] The most detailed account of this well-known propaganda is in Cynthia Marasigan’s 2010 dissertation from the University of Michigan, “‘Between the Devil and the Deep Sea’: Ambivalence, Violence, and African American Soldiers in the Philippine-American War and Its Aftermath,” pp. 62-67. “Gray” is presumably Edward Gray, lynched in Louisiana that June.

[3] See most recently his “Seeking David Fagen” in Tampa Bay History 22 (2008): 19-34, which includes all the information above. Schubert prefers to use the historically correct epithet, “bad nigger” (34).

The conclusion to a three-part sequence on “City of Refuge,” a 1925 short story by Rudolph Fisher. For earlier posts, please scroll down.

Earlier in this sequence of posts on Rudolph Fisher’s 1925 short story, “City of Refuge,” I discussed the blues historian Adam Gussow’s reference to a famous interview by Alan Lomax, in which the musician Jelly Roll Morton refuses to sing a lost song about Robert Charles, a legendary New Orleans fugitive.

The literary scholar Bryan Wagner has also written about this episode, comparing it with another famous anecdote told by Morton’s rival, W.C. Handy, the self-proclaimed “Father of the Blues”—a music he claims to have first learned from a “lean, loose-jointed Negro” casually singing and playing the guitar on the platform of a Mississippi train station.[1]

Wagner identifies this figure—the “ragged songster”—not as a real person, or even a specific invention of Handy’s, but as the necessary convention of a narrative. He is imagined by folklorists and blues collectors as the authentic source of the music because he is nameless and homeless, a cipher without any particular history or consciousness of his own worth knowing. He is indistinguishable from his song, because he sings what he does and does what he sings.

But Wagner’s most provocative insight is to connect this figure to its counterpart in the legal history of policing, which, he insists, is inextricable from the history of blackness more broadly. The police power, he argues, can be distinguished from the other ways institutions of law operate to produce what gets called justice. This power resists restrictive definition, and is accorded wide discretion, because it is understood to protect and defend the community against threats by deploying violence as deemed necessary, even preemptively.

For Wagner, the figure of black vagrancy featured in Handy’s anecdote, which is foundational to an entire array of histories of blues music and black culture, ought to be understood as a kind of formal convention given by the history of U.S. policing. It traces back to the regimes of slavery, when any white person was invested with the police power in relation to all black people. It is consolidated against the Jim Crow era’s black vagrant—that is, anyone the police chose to criminalize as inherently out-of-place and threatening, thereby subject to violence.

And it explains, among other things, why in 2015 it is so difficult to challenge the legitimacy of violence committed against black persons, by a policeman of any color, within the justice system.

From this perspective, withholding the Robert Charles song interrupts a procedure that is overdue for questioning. Independently of the race, intentions, good faith, or moral character of the blues collector, the protocols inscribed in his understanding of folk culture have their own effects. They obscure the work of the system that transforms violence into justice, celebrating a culture by removing its “treasures” from the very situations, social and historical and political, they name and engage and act upon.

You must ask, then, if the attempt to recover a lost song is merely another incursion into the everyday imaginative practices of the people whose can most clearly see and name this justice for the violence it is. How can the work of a scholar—whose own color, like the policeman’s, is at best a secondary matter—be other than plunder? Is it possible to respect the opacity of a figure like Robert Charles or David Fagen—to refrain from compelling it to sing—without overwriting its potential to act upon anyone within earshot, as the vehicle of a haunting by that which it works to keep concealed?

* * *

* * *

For the great scholar Alain Locke, whose intellectual P.R. efforts were central in defining what would become known as the Harlem Renaissance, the knowledge carried by a figure like King Solomon Gillis was epochal. The “migrating peasant [….] the ‘man farthest down,’” rushing to the industrial cities of the North and Midwest in droves, was reshaping the destiny of both the U.S. and the “Negro” race worldwide.

But in Locke’s view, the “great masses” were hardly “articulate as yet.” While the doctors, lawyers, and ministers of their Southern communities trailed meekly behind them, a different elite could give their thoughts expression—the college-trained intellectuals and young artists, like Rudolph Fisher, that Prof. Locke sought to mentor.

King Solomon Gillis, in other words, is an intellectual construct, a way to imagine someone in order to grant someone else the authority to narrate their consciousness. This imaginative work is a form of violence, which needs to be called out, even if I must admit—as an admirer of Locke and sometime practitioner of his profession—that it often requires great effort to keep from participating in it.

And this construct was not without its uses. The best-known writers to emerge from Locke’s milieu, Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston, sometimes occupied it and put it to use, even as their very existence undermined its presumptions. Similarly, the two best-known writers emerging from the colonial migrations of Filipinos to the U.S. accelerating in this period, Carlos Bulosan and José Garcia Villa, occasionally took refuge in the primitive, making the best of the only role metropolitan intellectuals offered them.[2]

In short, the migrating peasant or the primitive, like the vagrant, the ragged songster, and the badman, is among other things, a mask. In a famous essay, Ralph Ellison observed, “the Negro’s masking is motivated not so much by fear as by a profound rejection of the image created to usurp his identity. Sometimes it is for the sheer joy of the joke; sometimes to challenge those who presume, across the psychological distance created by race manners, to know his identity.”

Ellison, himself concerned to avoid the snare of folk authenticity he saw closing on himself and his celebrated novel, Invisible Man, sharply noted that this masking was “in the American grain,” citing such practitioners as Benjamin Franklin, Ernest Hemingway, William Faulkner, and Abraham Lincoln—not to mention Bulosan, Villa, and Phil Hartman. “America is a land of masking jokers,” he wrote.

But who gets to be in on the joke?

* * *

In the summer of 1901, a young black man calling himself Rube Thompson, outfitted in a blue, brass-buttoned coat, infantry hat, and long-topped shoes, was arrested in Pasadena, California on suspicion of stealing a bicycle. Variously reported as 20, 18, and 22 years old, he claimed to be on his way back home to Texas after two years in Manila, and his brash attitude and gift for fabulism initially dazzled the white judges, lawyers, and journalists he encountered in the sleepier reaches of the Los Angeles legal system.[3]

In his first appearance in the LA Times on Aug. 4th, a Justice Morgan is reported to be left “spellbound” and speechless by Thompson’s insouciant management of his own defense. Four days later, he appears pleading guilty before a different judge, who becomes suspicious of police misconduct and forces Thompson to confess, picking shyly at his “tattered soldier’s suit,”

“I’se a-pleadin’ guilty ’caz I haint got no witnesses an’ no lawyer.”

One is quickly appointed for him, and another attorney who happens to be present volunteers to assist in the case, leaving the police detective fuming.

But the story takes a more dramatic turn on Aug. 16th, when Thompson makes the remarkable assertion that he is actually none other than the notorious deserter and rebel, “John Fagens.” Though he got most of the names wrong, his confession demonstrated a detailed awareness of David Fagen’s publicly reported exploits, and an expectation, perhaps slightly exaggerated, that the local authorities would know of them as well.

Within a day, Fagens’s story fell apart, though it had already made its way into the San Francisco Chronicle, and was still working its way through newspapers in Hawai’i ten days later. The Times presumed he was scheming to get transferred beyond the reach of the local courts, whereupon the exposure of his identity might lead to his release. The historian Timothy Russell, who uncovered his story, has verified that a “Reuben Thompson” was employed as a teamster by the U.S. Army Quartermaster in Manila from November 1899 to April 1900. Of course, this identity could have been appropriated, too; in any case, the alleged bicycle thief is last glimpsed in the record on his way to a two-year sentence in San Quentin.

Frank Schubert has turned up a related, if clearly apocryphal, story about David Fagen’s father, who died after his seventh son came home from a tour with the 24th Infantry in Cuba, but prior to his reenlistment and departure for the Philippines. In a 1959 volume of Florida history, Sam “Fagin” is falsely depicted as “a shiftless old Negro who was never known to work, but had about 20 children.”

Hauled to court on a charge of chicken-stealing, he’s so unnerved by the stern judge that he confesses, but his white lawyer quickly intervenes to enter a plea of not guilty. In response, the judge, citing his proud South Carolina heritage, immediately dismisses the case: for how can he take the word of a black man over a white man?[4]

It is not so strange, I suppose, that the myth of David Fagen would draw stories like these in its wake, as if magnetized by their shared themes of racial masquerade, deception, and escape. But is it an accident that the most definitive imagination of a successful getaway appears in the story that, beyond the flimsiest pretense of historical details, is so clearly just a retelling of an old racist joke?

* * *

You:

“invisible things are not necessarily ‘not-there’”

The Library:

Just because you can’t see it doesn’t mean it isn’t.

You:

“nothing that has ever happened should be regarded as lost for history”

The Library:

Sometimes being lost is the condition of refuge.

You close your eyes and push on the wall

it moves

and the music!

* * *

In his dazzling book of criticism, The Grey Album, the poet Kevin Young identifies three types of “shadow books” that haunt black literature.

The first,

promised or proposed or begun and abandoned,

is the unwritten.

The second,

described or alluded to or even

quoted in an existing text, but teasingly

withheld, so that

so that its actual nonexistence becomes

a way of making meaning, resonating

with the blindspots and erasures

of knowledge and perception that

for better or worse

race establishes,

is the removed.

And the third,

the most straightforward and bedeviling,

is the lost

—once written, but no longer extant.[5]

It would be difficult to find a more prolific author of shadow books than Carlos Bulosan, whose published and unpublished writings abound with references to works in all three categories—sometimes, paradoxically, all three at once. The Rosetta stone of his shadow oeuvre is an April 8, 1955 letter he wrote to Florentino B. Valeros, located in his papers at the University of Washington Libraries and published as an appendix to All the Conspirators—which was itself once one of his shadow books, recovered in his papers bearing the byline “Dunstan Peyton” and published three decades after his death.

Bulosan opens the letter by explaining he’s just arrived in the union office (ILWU Local 37, Cannery Workers) from jail, adding ambiguously:

“When a person just came out of jail (drinking?)

his mind wanders in a nightmare

that pursued him the night before.

Now a long time ago I made a resolution never

to reveal certain facts of my personal life;

I resolved also not to give to anyone

a complete bibliography of my published writings.”

But he allows that he’ll make an exception for Valeros’s wife Margarita, who is preparing a thesis on his work.

He then unleashes a brilliant, rambling, sometimes vague and incomplete, and occasionally demonstrably false accounting of his bibliography. He refers to poems and stories and books he has lost, forgotten, planned, and failed to write, as well as two books for young readers that, if they exist, were likely written by someone else.

Eventually, the text drifts off in a digression about how much alcohol he claims to be capable of drinking, breaking in mid-sentence at the end of the page. It picks up again, perhaps a day later, in a more ordered list that finally teeters and trails off the page:

This letter, which I’d argue should be read as a statement of Bulosan’s rigorous commitment to an aesthetics of labor migrancy, is worth at least a full post on its own. But in closing this one, I want to turn from his shadow books to the one book by Bulosan that readers are likely to know, his 1946 “personal history,” America Is in the Heart.

In one of its most famous lines, the narrator describes how, as a migrant in the 1930s metropole, he came to understand:

“it was a crime to be Filipino in California.”

The occasion for this insight is his experience of police harassment for Driving While Filipino—

“the public streets were not free to my people:

we were stopped each time

these vigilant patrolmen saw us driving a car.”

Or, as his companion Doro explains,

“They think every Filipino is a pimp[….]

I will kill one of these bastards someday!”

Because anti-Filipino racism in the U.S. no longer takes quite the same form it did before World War II, it is easy to overlook its relationship to antiblack racism in this period. What they share is the structure of an overwhelming, sexualized violence, manifested in lynching and colonial warfare.

Those placards proclaiming vengeance for Sam Hose, left for black soldiers outside Manila, aimed to make this link visible, and it is this link that is presumed every time the story of David Fagen is invoked. The vengeance Doro imagines, perhaps, is something like the fate of Robert Charles, as narrated by Ida B. Wells-Barnett:

“Betrayed into the hands of the police, Charles, who had already sent

two of his would-be murderers

to their death, made a last stand in a small building,

1210 Saratoga Street,

and, still defying his pursuers, fought

a mob of twenty thousand people,

single-handed and alone, killing

three more men,

mortally wounding

two more

and seriously wounding

nine others.

Unable to get to him in his stronghold, the besiegers set fire to

While the building was burning Charles was shooting,

and every crack of his death-dealing rifle added another victim to

the price

which he had placed upon

his own life.

Finally, when fire and smoke became too much

for flesh and blood to stand, the long sought for

fugitive appeared in the door, rifle in hand,

to charge

the countless guns

that were drawn upon him. With a courage which was

indescribable,

he raised his gun to fire again, but this time it failed, for

a hundred shots riddled

his body,

and he fell

dead

face fronting

to

the mob.”

* * *

What is the difference between security and refuge?

In the history of the blues, as written by its devoted collectors, the song of Robert Charles ranks in the canon of shadow books. But the great and tragic joke of the quest to recover it is that the song of Robert Charles is not so much lost as ever-present.

It’s anywhere you want to look or listen, in the history of black music from 1900 to the present, and as you read this, it is being recomposed and rearranged, recorded and uploaded, in Florida and Missouri and Ohio, in South Carolina and New York and California, in Minneapolis and Chicago and everywhere else. (When the fire starts, who’s to say where it will stop?) If you cannot hear it yet, you may at least lift your head and give a nod to our visitors from the future, trawling in the digital archives, those historians of whatever it is that comes after hip-hop.

Don’t credit too much what I am about to say next, for I am too poor a reader sometimes. But I have never quite been able to catch the feeling for utopia, which has always sounded to me like the gated community of the radical imagination.

I prefer to dream of a vast electronic library of shadow books. Would you lose yourself in its stacks? Even there, the dissertations gather dust: they are ballast, or they are kindling. (That must a fourth category—the books that have been written that no one ever bothers to read.)

In my mind, I close the cover, and lay one more title onto the pile:

Robert Charles’s City of Refuge, Carlos Bulosan’s Crazy Blues.

Would you bring an ark, or a match?

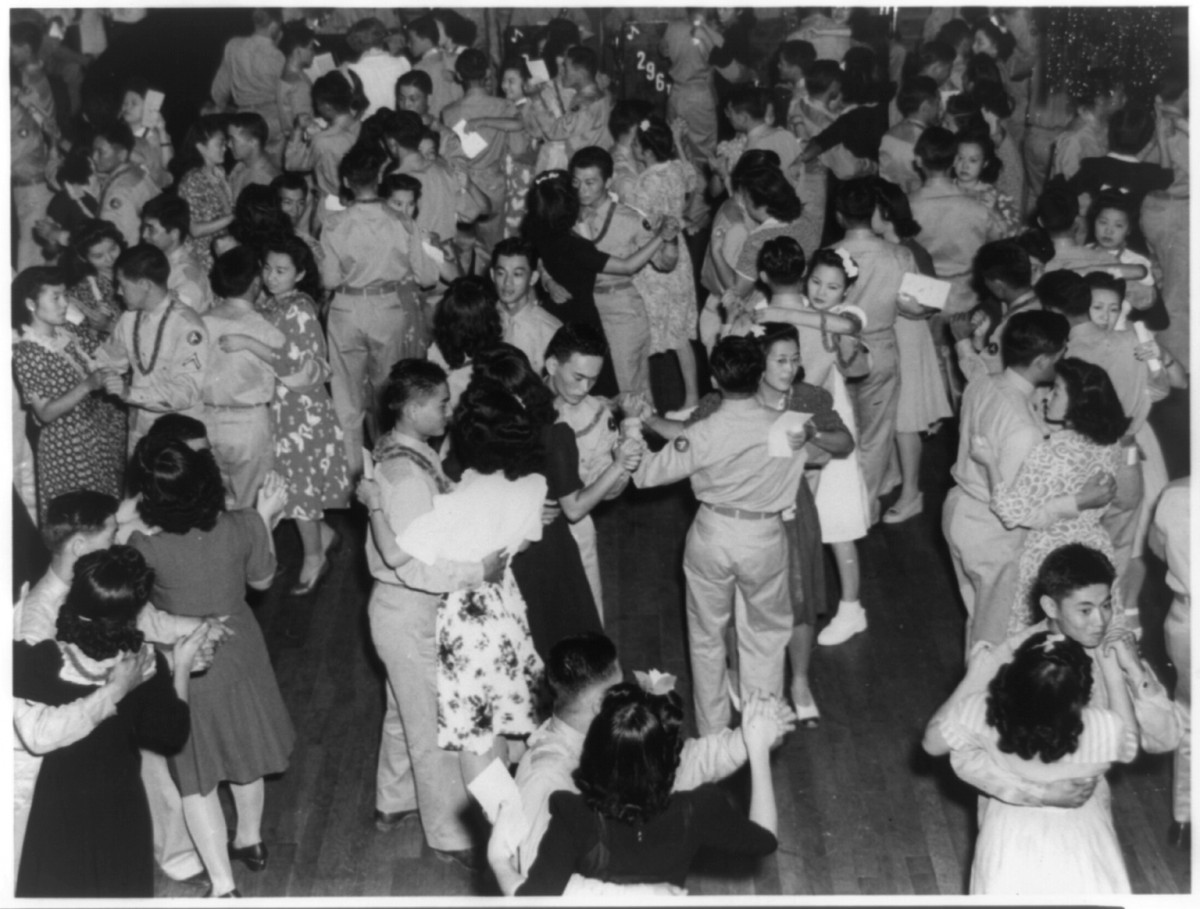

Chicago, c. 1950

Vincent T. Tajiri Estate

Welcome to the City of Refuge! Coming next week, a new sequence on the lost Afro-Asian century, featuring W.E.B. Du Bois, Philippine-Ethiopian intrigues, and the transpacific antecedents of Afrofuturism.

New posts appear here every Wednesday, through the end of the year. Read with me, and tell me about it—a comment section should appear below if you’re signed in to Facebook, but you can always reach me here and here.

[1] Even in myth, the shadow of empire: Handy associates the man’s technique of pressing a knife on the guitar strings to “a manner popularized by Hawaiian guitarists,” as quoted on p. 26 of Wagner’s Disturbing the Peace: Black Culture and the Police Power after Slavery, Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 2009. Chapter one deals with Handy, Morton, and Charles.

[2] I’ll have more to say about this in a later post. But get the conversation started, if you’re inspired!

[3] See Timothy Russell’s 2013 dissertation from the University of California, Riverside, “African Americans and the Spanish-American War and Philippine Insurrection: Military Participation, Recognition, and Memory, 1898-1904.” Coverage of the case can be found in the LA Times of August 4, 8, 16, and 17, 1901, and the August 16 LA Herald, as well as less substantive coverage in the August 16 San Francisco Chronicle, August 26 Pacific Commercial Advertiser (Honolulu), and the August 27 Hawaiian Gazette.

[4] See Schubert 21; he notes that Sam Fagen bore little resemblance to this figure, and that the same anecdote can be found elsewhere with different characters.

[5] See Young, The Grey Album: On the Blackness of Blackness, Minneapolis: Greywolf, 2012, pp. 11-14. The book’s comments on Mamie Smith’s “Crazy Blues” (esp. 159-65) are very much worth discussing, but I’ll hold off for now.

This is the first installment in a sequence on the geography of the lost Afro-Asian century. Scroll down for older posts, and come back for another installment next week.

Back to the land of California

To my sweet home, Chicago

—Robert Johnson

Chicago, my hometown, I miss you dearly. But goddamn you are racist and corrupt as hell.[1]

The man who’s supposed to run you owes his seat to the cover-up of a murder, the arbitrary and gratuitous execution of a boy, and now the whole world knows. The sport of it, now, Chicago, is to watch the fix as it plays out in plain view, in slow motion, to watch and see who gets sacrificed to preserve whose power, and how quickly the breach can be closed, if there even is one, in the brutal business of the city.

But even if he falls, Chicago, he is only the expression of your own vicious heart. What god could be blamed for visiting you now with fire?

Chicago, did you ever want to be free?

* * *

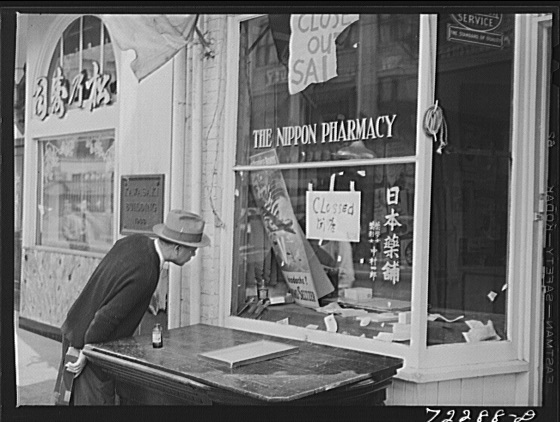

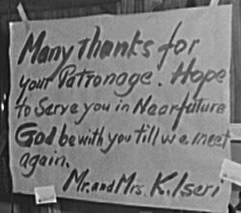

Once upon a time, Chicago, you were the city of refuge, for my grandparents, and for a whole generation of Japanese Americans looking for a way out of the camps where they’d been locked up by their own government. You were no kinder then, just younger and more wide open, and there was a war on and so much of a world for the taking.

The well-intentioned liberals who ran the wartime incarceration regime and its offshoots promised that it was the very best of the Nisei they were sending you, American-born children of Japanese immigrants who worked hard and loved baseball and swing music and everything else you said you did, and you could count on them to be first in line to die for it.

To be honest, they didn’t really want the Nisei to get bunched up in one place like they did. They’d chosen the best specimens to send out in an advance guard from the camps, and encouraged them to spread out in twos and threes across the heartland. If these Japanese just learned not to throng together like they did in their old colonies along the West Coast, they reasoned, they’d dissolve into Middle America like sugar in a white girl’s mouth.

But this wasn’t the sort of idea that survived a few days in the sun, and so the Nisei “resettlers” mostly found their way to you, Chicago, and, then as now, you were willing to tolerate the fine visions of liberal do-gooders as long as they didn’t require you to pay much notice. So my grandfather, a soldier, and my grandmother, a Poston beautician with a degree from the San Francisco School of Beauty Culture, slipped into your shadowy assembly.

Chicago, did you ever want to be free?

* * *

When they got to Chicago, my grandfather didn't work for a year. Instead, he went to the beach every day, my aunt says he told her, thinking about what he was going to be. He got a job as a civil servant, then backed out at the last minute. He took a class in photography, but he knew more than the teacher.

You're a photographer, Chicago told him, won't you admit it? What else could he be, when the city winked at him like this?

Photo credit: Vincent T. Tajiri Estate

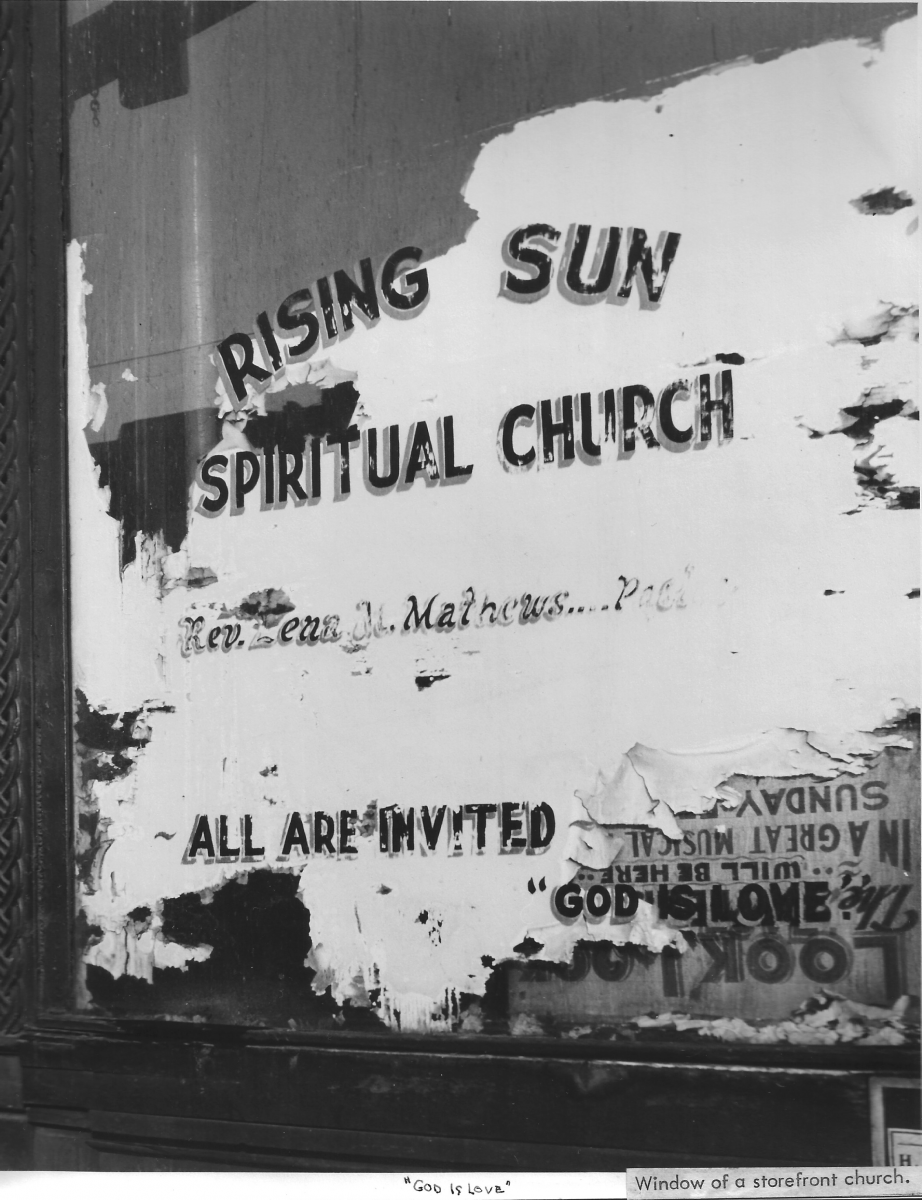

Reader, if you know anything about

this image, please let me know.

I assume that this reference to the rising sun had nothing to do with Japan. But I would not be surprised if my grandfather was aware of the deep current of pro-Japanese sentiment that ran through prewar African American communities.

Stemming at least as far back as the 1904-05 Russo-Japanese War, it found adherents in all regions and strata of black society, though by the mid-1930s it seems to have been strongest in working-class milieus, blending politics and religion, running a circuit from the Great Lakes down to the Mississippi Delta.

It was suppressed, of course, during the war, through the extensive and coordinated activities of federal and state officials from Chicago to East St. Louis and New Orleans, and from Kansas City to D.C., Harlem and Newark. Mortified, the black elite did its part to put down and stamp out these seditious sympathies.

Among other things, their concerted effort helped an up-and-coming young college teacher named S.I. Hayakawa land a column at the Chicago Defender. There, he reassured readers of the leading black newspaper that the Nisei were loyal Americans, and that well-meaning white Americans would do more for them than “the whole Ethiopian army or Japanese navy.”[2]

In time, I will have more to tell you about Hayakawa and my grandfather, about black sympathies for imperial Japan, and why the specter of an Ethiopian army keeps leading me back to the Philippines. For now, I just want to pause over this image. It must have given him a smile.

What would he have been thinking, behind that smile?

Without question, my grandfather would have found himself on the side of all those African Americans and Japanese Americans eager to bury any hint of pro-Japanese sentiment. Indeed, those were the terms on which Negro-Nisei civil rights coalitions would, for at least a few years, be built.

Raised on a predominantly African American block in multiracial south central L.A., he must have felt some degree of familiarity within Chicago’s communities of black Southern migrants. Not out of some special affinity for black folks—despite the prescriptions of the liberal theorists of assimilation, the urban segregation he’d always known still tended to herd nonwhite communities together. And he’d come to Chicago from Mississippi himself, having done most of his military service at Camp Shelby since his health precluded him from combat overseas.

And he was decidedly not religious, despite having acquired a Catholic “American” name. Why, then, did he emphasize the phrase, “God is love”? Was this another joke, or an appreciation? Or just a way of deflecting attention from the joke of the church’s name?

“Look Look,” calls the sign, upside-down, behind glass, in the corner. What is it calling you to see?

* * *

Of the boy who was killed, a ward of the state: he should not be denied his name. It is wrong not to say his name, and it is wrong again to say it. Every repetition of his name bears forward the work of his killers, that violence through which you and I are called upon to perceive and make sense of the world, and if there is another world where calling his name might bring him justice, may you live long enough to see it.

If there is any justice to be found, in this world, it will come for everybody else, in his absence, because this is what it means to ask for justice in the name of the dead. Of course, what is true for the dead is merely the end of an illusion maintained by the living—that your name is your very own, when instead, like your very identity, it belongs to everyone else but you. This is why I keep hesitating every time I start typing his name. To write it would only repeat the way that his life been given away to everyone but himself.

It is wrong to say his name, and it is wrong again not to say it. This is the case, simply put, because it is the world you and I are in that is wrong, the world where he is not, and no one has figured out yet how to put it right. To act at all in this world is to be in the wrong, but one must still act; and so I choose not to write his name, and instead ask you to speak it, aloud, in silence.

* * *

On Sunday, there will be music—this much you can still make out. “Look Look,” it says behind the glass.

* * *

Chicago, capital of the lost Afro-Asian century, on what map could I find you?

(Will I have to listen to that song again? What kind of Chicagoan isn’t tired of that song?)

Bear with me, reader. This is an essay on the geography of that lost century, but it is also a personal history, and for me, everything will keep on ending in Chicago.

It will begin in the Philippines, or it will begin in Georgia. It will begin, as you might expect, in an act of overwhelming violence. And it will go wherever the music will take you.

Meet me here next week?

* * *

Welcome to the City of Refuge! Coming up in this sequence: further explorations of blues music, secret identities, bitter jokes, and geopolitical intrigue, with appearances by Robert Johnson, W.E.B. Du Bois, Emilio Aguinaldo, and Emperor Menelik II of Ethiopia.

New posts every Wednesday, through the end of the year. Read with me, and tell me about it—a comment section should appear below if you’re signed in to Facebook, but you can always reach me here and here.

[1] I won’t link to the video here. If you can watch it without being traumatized or indifferent, you should; it’s no trouble to find. But this is for everybody.

[2] S.I. Hayakawa, “Second Thoughts.” Chicago Defender 16 June 1945: 17.

This is the second post in a sequence on the geography of the lost Afro-Asian century. Scroll down for older posts, and come back for another installment next week.

Years later, I made it back home to California.

Happy birthday, Shinkichi Tajiri!

* * *

When, as a young man, I went off to school in a cold, grey Midwestern town, blues music became the vehicle of my homesickness. Chicago blues I liked well enough, but it was other sounds that carried me—Lightnin’ Hopkins, John Lee Hooker, the late recordings of Son House. Music of displacement, of people who made their own maps.

Well. I’m old enough now to know that, really, nobody wants to hear about the music you liked in college. And if I’m being honest, Robert Johnson was never quite my favorite. But his version of “Sweet Home Chicago” haunted me for years.

Long before it became a blues standard—if not a grating cliché—Johnson recorded the song in a San Antonio hotel room in 1936. A Delta-based itinerant musician whose travels took him as far as New York, Canada, and Chicago, Johnson’s dazzling technical abilities and early death have made him, for better or worse, a figure of legend.

In his version, sweet home is not an origin, but a destination: the singer seductively invites his listener to leave the place they are in, and come with him to the more glamorous locales he proclaims his own. Don’t you want to go, he asks,

Back to the land of California, to my sweet home Chicago.

Long after his death, this line would cause untold vexation for many of Johnson’s most fervent devotees, who have gone to great lengths to banish the thought that he might have been so ignorant of basic geography as to place Chicago in California.[1]

Of course, he wasn’t. The problem isn’t necessarily that blues historians condescend to the people who made the music they love, though they too often have. Rather, as I discussed in an earlier post, the very concept of authenticity through which the blues has been defined as a distinct cultural tradition tends to imagine a songster unencumbered by modern knowledge.

For the same reason, discussions of Robert Johnson conventionally require some reference, leg-pulling or dismissive, to the old myth that he acquired his talent for guitar by selling his soul to the Devil at a crossroads one midnight. It’s easier to wrestle down this old hackneyed story, it seems, then to face the reality that the bluesman shared a world with you, that his craft required intelligence, that he earned his skill with diligence. It’s easier to spend a lifetime chasing his shadow than to recognize that the distance, from there to here, can be bridged in a simple instance of parataxis.

* * *

But to me, the song was always a map. In its geography of yearning, I would eventually discover my own family’s history.

For poor African Americans in the Mississippi Delta in the 1930s, California and Chicago were places of refuge, homelands of the future where the migrants streamed in flight from poverty, arbitrary imprisonment, and state violence and its counterpart in lynch law. World War II brought a new phase of this Great Migration, swelling the seams of black Chicago and bursting them in Los Angeles, where the segregated areas vacated by incarcerated Japanese Americans became overcrowded with new arrivals from the South.

As the war progressed, the liberal stewards of the incarceration regime sought to empty the camps and engineer the redemption-by-assimilation of loyal Japanese Americans, dispersing them across the country, as far from their old West Coast ghettoes as possible. In Chicago, the arrival of “resettlers,” like my grandfather and his family, was meant to be carefully distinguished from the “race problem” presented by the ongoing black migration.[2]

Meanwhile, back in L.A., “Little Tokyo” was being rebranded as “Bronzeville.” But to skeptics like the great novelist Chester Himes, this bit of boosterism could not erase the fact that black migrants had merely taken up residence in a “race problem” previously mapped as Japanese. Himes was a recent arrival himself, a faculty brat from Missouri and the Arkansas delta who’d survived a fall down a Cleveland elevator shaft and terms in Ohio State University and the Ohio State Penitentiary. In L.A., he rented the home of the Nisei writer Mary Oyama Mittwer, who became a close friend.

A few months after I was born, my grandparents moved back to California, leaving us behind in the crumbling house they’d bought in Rogers Park on Chicago’s Far North Side. Other than Toguri Mercantile on Belmont Ave., the mysterious Nisei Lounge near Wrigley Field, and the occasional name on a dentist’s or optometrist’s practice, I grew up unaware there was ever a vibrant Japanese American Chicago. And in L.A., Little Tokyo was all too happy to forget it was ever Bronzeville.

Even so, the song stayed with me. I listened to it again and again, distractedly, the way you might stare into the dark glass of an abandoned storefont every afternoon, riding home on the bus. Day by day, month by month, it comes to you slowly that there might be someone else there, on the other side of history, You can’t see them and they can’t see you, but look look—their eyes and yours, all this time, have been trained to the same place.

* * *

What became of this geography of longing—how it ended, as it always does, in Chicago—I will come to in a later post. I haven’t even got to the beginning yet—that will have to wait, too. But first, I need to explain the difference between sweet home and back home.

In the same 1936 session in San Antonio, Robert Johnson recorded another blues classic, “I Believe I’ll Dust My Broom,” whose equally distinctive cartography has drawn much less attention from scholars.

The colorful phrase in the title, “dust my broom,” refers idiomatically to the singer’s desire to finally be done with his unfaithful lover—to leave her and go “back home” where she can no longer mistreat him. It’s a classic narrative of modern life as an experience of moral degradation, contrasting the lover who cannot be trusted to the nostalgic ideal of a “good girl” to whom he can return.

This is not a story of a Great Migration north, however. If sexual immorality is a condition of modern urban life, the singer doesn’t have to go to Chicago to find it. What’s more, this “good girl” appears to be suspiciously elusive; though he’s sure he’ll find her, she’s always just out of reach. At first, he goes looking in “West Helena” and “East Monroe,” adjacent towns in the Arkansas Delta, but by the last verse, his search seems to take him to the ends of the earth—the location names are replaced with China, the Philippines, and Ethiopia!

In the standard transcription of the lyrics, these place names are presumed to be meaningless. “China” appears twice, the first time as “Chiney,” and the Philippines becomes “Phillipine’s Island.” A footnote in the booklet accompanying Johnson’s complete recordings explains that these are “not typographical errors, but simply approximations of how Johnson pronounced” them.

While you can hear a difference between the two instances of China, however, similar differences in the pronunciation of “California” in “Sweet Home Chicago” are not orthographically marked. And while the addition of an apostrophe in “Phillipine’s” is arguably justifiable as a quirk of vernacular speech—growing up in Chicago, I remember all kinds of proper nouns picking up a spurious apostrophe-S as a matter of course—the added L and missing P in the word is not.

What these errors reveal, in short, is the inadvertent condescension of Johnson’s devoted followers to the knowledge circulating in his Delta milieu. For it is easier, apparently, to believe that these names are sheer nonsense than to imagine that an itinerant black musician and his Southern audiences might have a richer awareness of geopolitics than that of his dedicated scholars.

If you instead begin from the assumption that these names have meaning, points of reference are simple enough to find. To say that the 1935-36 war between Italy and Ethiopia was front-page news for African Americans is an understatement. The ill-fated defense of the esteemed independent African empire against Mussolini’s colonial forces commanded the attention of black people around the world. One major subplot in its narrative was the prospect, ultimately dashed, of a Japanese intervention on Ethiopia’s behalf, given existing diplomatic ties between the two prominent nonwhite empires.

Meanwhile, the Philippines, still under U.S. colonial rule, would hardly have been obscure to African American communities. The participation of black soldiers in the U.S. conquest and occupation was still a living memory. This recollection would have been regularly refreshed by black press coverage of colonial affairs and anti-Asian movements on the West Coast. Just two years earlier, the passage of Tydings-McDuffie Act promised Philippine independence in a decade, while effectively ending labor migration from the colony.

The fine scholarship on Johnson’s song suggests persuasively that the reference to China had an independent origin—it appears Johnson revised a verse mentioning China from Kokomo Arnold’s “Sissy Man Blues,” adding the Philippine and Ethiopian references. In earlier songs, this “China” is a figure of pure exoticism—the other side of the world, the place you could reach by digging. But the new context changes its meaning. For example, the rising leftist element in African American politics, which also looked to Asia for allies against white supremacy, often reappropriated black speculative imaginings of Japan, substituting China in the name of a broader anti-imperialist politics.

It would be going too far to attribute an explicit radical agenda to Johnson’s song, or even to presume that Johnson intended these names to refer to geopolitical events. Authorship in blues music of this period, however, cannot be reduced to an individual consciousness. These songs are collective creations. Songs were borrowed and revised, specific verses floated from one song to the next, and the participation of audiences shaped what a singer recalled and repeated from one performance or recording to the next.

In short, the song expresses a collective knowledge of world events, as well as a politics of race, gender, and desire, within the black communities that the Delta-based Johnson traversed—communities that were themselves always on the move. And perhaps it should not be surprising that a juke-joint or street-corner audience in Depression-era Arkansas might know more about contemporary world events than a later generation of scholars, raised and educated in a dominant global superpower. For black people in the 1930s, it was much more reasonable to imagine that some foreign entity might intervene in the conditions of their oppression with superior force.

And indeed, the same communities where Johnson plied his trade had also proved fertile territory for a loosely connected network of radical organizations, built on foundations laid by Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association, that preached an Afro-Asian alliance against white imperialism. These networks mixed religion with politics, promoted an internationalist black nationalism, and blurred the lines between confidence schemes and earnest revolutionary aspirations.

Operating from Harlem to Detroit, Chicago to New Orleans, and Oklahoma City to St. Louis, groups with names like the Peace Movement of Ethiopia, the Ethiopian Pacific Movement, the Development of Our Own, and the Original Independent Benevolent Afro-Pacific Movement of the World, Inc., were organized by a fascinating and shadowy assortment of working-class black, Asian, and Latino men and women. Fiercely suppressed for seditious Japanese sympathies during World War II, they were typically short-lived and quickly forgotten—with the exception of the various iterations of Elijah Muhammad’s Nation of Islam.[3]

The relevance of this history to Johnson’s lyrics is apparent—just to take one example—from the program of a 1933 event at a St. Louis church, which featured presentations from three members of the Pacific Movement of the Eastern World. George Cruz addressed “Why the Filipinos Want Freedom,” Moy Wong spoke on “The Old and New China,” and their leader, Dr. Ashima Takis, took up “The Struggle of the Darker Races of the World.” As far as contemporary scholars have been able to determine, the supposedly Filipino Cruz was, in fact, a Japanese American, while the notorious Dr. Takis, posing as Japanese, was actually a Filipino man named Policarpio Manansala!

* * *

Over the years, as I have listened to these songs, and wandered lost through the records of this Afro-Asian world scattered in scholarly publications, old newspapers, and the less reliable corners of the internet, I’ve found myself wondering, not what Robert Johnson may have thought when he sang these words in that hotel room in Texas, but what his audiences must have been thinking when they heard him play. Perhaps you'll have a listen yourself, and tell me what you think?

If sweet home is just a dubious promise of the future, and back home an elusive fantasy of the past, what happens when they switch places?

If West Helena and East Monroe, Arkansas, can become China, the Philippines, and Ethiopia in the time it takes to play an old phonograph record, how long would it take me to travel from there to here?

Phillipine’s Island, as far as I know, is not a place recorded on any map, in Arkansas or Mississippi or anywhere else. But if you leave West Helena and head north up the river in the direction of St. Louis and Chicago, and you make it as far past Memphis as it took you to get there, then off to the west, across a little cluster of lakes, you’ll find a little town called Manila, Arkansas, incorporated July 3, 1901.

Whether Robert Johnson, George Cruz, Policarpio Manansala, or my grandfather ever set foot in this Manila, I do not know. But if they had, they would have been sure not to stay the night, because Manila was what used to be known, in that quaint American vernacular, as a sundown town.

* * *

When I was in college, and I first learned that Mike Masaoka, the controversial Japanese American Citizens League leader, titled his autobiography They Call Me Moses Masaoka, I couldn’t help but think of the story of Japanese American incarceration and resettlement as an exodus story. Because, growing up in Chicago, I imagined that my family was part of that branch that got stranded in the desert, wandering lost for decades without making it home.

It was silly of me, I realize now, but I was still in the Midwest when I learned all this. It didn’t occur to me until decades later that California is a desert too.

* * *

Welcome to the City of Refuge! Coming up in this sequence: W.E.B. Du Bois and the origins of the lost Afro-Asian century, and a possible escape route from the century’s end in Chicago.

New posts every Wednesday, through the end of the year. Read with me, and tell me about it—a comment section should appear below if you’re signed in to Facebook, but you can always reach me here and here.

[1] For one, remarkably thorough explication, see Max Haymes.

[2] Jacalyn Harden’s 2003 volume, Double Cross: Japanese Americans in Black and White Chicago, has been subjected to much criticism in Asian American studies for its treatment of a respected elder, Prof. Setsuko Matsunaga Nishi. Setting that controversy aside, I want to express my deep appreciation for that book—finding it in graduate school gave me back my hometown.

[3] The best scholarly work on these groups remains that of Ernest Allen, but exciting new ground is being broken by emerging historians like Keisha Blain.

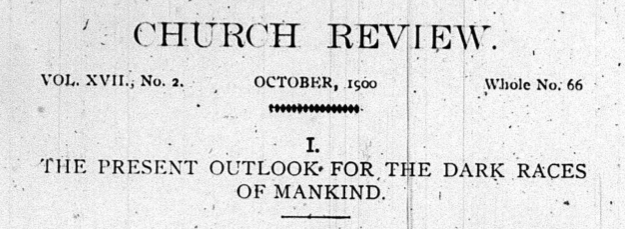

The third installment in a sequence on the geography of the lost Afro-Asian century. For earlier posts, please scroll down.

The Afro-Asian century begins with a prophecy. The lost Afro-Asian century begins with a joke.

* * *

“This outrage unhappily is only one in a series.”

* * *

And it begins,

“for the problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the color-line.”

Here, in the first paragraph of his epochal 1903 volume, The Souls of Black Folk, the scholar and activist W.E.B. Du Bois lays down the claim that would bind his own life to the course of an era.[1]

After this warrant of an introduction, Du Bois repeats the phrase twice more in the book.

“The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color-line,”

begins his second chapter, “Of the Dawn of Freedom,” and he continues with a brief gloss on the phrase:

—the relation of the darker to the lighter races of men

in Asia and Africa, in America and the islands of the sea.”

But this is only meant as a way of framing the history his essay recounts, of the unfinished work of post-Civil War reconstruction, as you may see by the repetition in the chapter’s closing words:

“The problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the color-line.”

Three years earlier, in London, at the landmark First Pan-African Conference of 1900, Du Bois authored a collective statement, “To the Nations of the World,” which also established its grounds by proclaiming,

“The problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the color line,”

or, slightly more effusively,

“the question as to how far differences of race,

which show themselves chiefly in the color

of the skin and the texture of the hair,

are going to be made, hereafter, the basis

of denying to over half the world

the right of sharing to their utmost ability

the opportunities and privileges of modern

Though the statement explicitly addresses “the Great Powers of the civilized world,” its greater aim is to conjure into presence a collective speaking subject, “the men and women of Africa in world congress assembled,” capable of articulating its own political interests. It invites “the millions of black men in Africa, America and the Islands of the Sea” less to hear themselves addressed than to hear this voice as their own.

You may have recognized by now that the power of this statement may have something to do with repetition. And if you have any familiarity with writing on the topic of race, you’ve heard it quoted more times than you care to remember, usually at the introduction or conclusion to a book or lecture or essay.

This iterability was no accident. Du Bois understood the political force of a “pert and singing phrase”—he could have accomplished a lot with Twitter—and the genius of this formulation is that it does much of its work whether or not its speakers understand what they are repeating. In fact, it seems he was quoting himself the whole time.

As far as scholars have been able to determine, the origin of Du Bois’s famous color-line formulation is a little-known address he delivered on December 27, 1899 in Washington, D.C., to an organization of intellectuals, the American Negro Academy. The phrasing is not quite as succinct and elegant in this text—it takes him over a paragraph to get to the first version:

“the color line belts the world and the social problem of the twentieth century

is to be the relation of the civilized world to the dark races of mankind,”

and the payoff, a few pages later, still walks with a hitch:

“the world problem of the 20th century is the Problem of the Color line.”

Yet a full reading of this text is a revelation, for here the formulation is no mere catchphrase, but the thesis of an argument to be carefully explained and established. This thesis is the prophecy of an Afro-Asian century. And its occasion is the Philippine-American War.

* * *

“this civilized Christian nation is expected to rejoice”

* * *

The Afro-Asian century begins here, but this beginning was easy to miss.

The address in D.C., truth be told, was a relatively minor episode in an utterly wrenching year for the Atlanta University professor. On one hand, Du Bois’s academic career had reached new heights, repaying years of struggle. He was contemplating a generous offer of employment from the most powerful black man in the country, Booker T. Washington—soon, he’d become known as Washington’s greatest adversary—and holding out for better.

On the other hand, he was shaken by the nearby lynching of Sam Hose that April, an atrocity that reverberated from Georgia as far as Luzon, as I discussed in an earlier post. Du Bois’s close encounter with the public display of a gruesome trophy from Hose’s killing fractured his faith in his scholarly endeavors.

One month later, he witnessed the brief illness and death of his son Burghardt, barely two.

(White doctors in Atlanta would not treat black patients, and black physicians were in short supply.)

Meanwhile, lynching—as the Sam Hose case illuminated—found its analogue in the brutal violence of the American war of conquest in the Philippines. As a sequel to the conflict with Spain, the war quickly became unpopular among African Americans, who recognized its white-supremacist underpinnings. But few held much hope that this resistance would prove effectual.

Stepping back, it is difficult not to imagine this moment as one of despair—of the rise of Jim Crow and of empire, of what seemed to be the final betrayal of the hopes of Reconstruction. The African American historian Rayford W. Logan would later famously term this broader era, “the nadir.”

In the definitive two-volume biography of Du Bois by David Levering Lewis, the 1899 address does not merit a mention. The sole book-length history of the American Negro Academy even contradicts itself, in a single chapter, on the question whether Du Bois even attended the year’s meetings.[2]

* * *

Jauntier days:

Going over Niagara, 1905

Library of Congress

* * *

The only extant text of Du Bois’s 1899 address, “The Present Outlook for the Dark Races of Mankind,” was published the following autumn in the Church Review, an A.M.E.-affiliated journal edited by Hightower T. Kealing. A whirlwind survey of “the problem of the color line […] in its larger world aspect in time and space,” it guides its readers through analyses of racial conflicts across five continents, and of world-historical dynamics over four centuries.

Beginning in Africa, and traveling across Asia and the Pacific to South America and the U.S., it culminates in Europe, where he lays down his now-famous thesis. The color line, it turns out, is not a bar to be lifted or crossed over, but a traveling analytical concept for considering how race is made and remade, in uneven and unpredictable ways, across a global field of imperial competition.

The problem of the color line, as Du Bois defines it, is a crisis of accelerated geopolitical competition that generates intensified processes of racialization within imperial states, at their borders and at their centers. Race, in this crisis, is a something like a technology for legitimizing both conquest and mastery, in putatively biological and cultural terms. But because its ultimate horizon is global—because race provides a language of justification and justice that extends beyond the reach of any one imperial power—it offers the possibility of unexpected forms of connection and correspondence from below.

In short, the problem of the color line means that the very justifications of world-grasping white-supremacist imperialisms provide the terms for racialized minorities and colonized populations to construct relations with each other to overcome their domination by Europe and “Anglo-Saxon” America.

For Du Bois and his American Negro Academy audience, he asserts, the revelation of this possibility is given by the very event dominating newspaper headlines and black public and private debates: the Philippine-American War.

Though he explicitly opposed it, here he takes conquest as a fait accompli, in order to imagine adding eight million Filipinos, along with a lesser number of other new colonial subjects, to a population of nine million African Americans:

“But most significant of all at this period is the fact

that the colored population of our land is,

through the new imperial policy,

about to be doubled

by our ownership of Porto Rico,

and Hawaii,

our protectorate of Cuba,

and conquest of the Philippines.

This is for us

and for the nation

the greatest event

since the Civil War.”

This revelation allows Du Bois to imagine an antiracist coalition under empire:

“Negro and Filipino,

Indian and Porto Rican,

Cuban and Hawaiian,

all must stand

united

under the stars and stripes”

[.…]

“nearly twenty millions

of brown and black people

under the protection of the American flag

a third of the nation”!

But this new situation establishes a greater moral responsibility upon his fellow African Americans, on whose leadership depends not only “the ultimate destiny of Filipinos, Porto Ricans, Indians and Hawaiians,” but also “in a large degree the attitude of Europe toward the teeming millions of Asia and Africa”—

“No nation ever bore

than

we black men of America,

and if the third millennium of Jesus Christ dawns,

as we devoutly believe it will

upon a brown and yellow world

out of whose

advancing

civilization

the color line has faded

as mists before the sun—

if this be the goal

toward which

every free born American Negro

looks,

then mind you,

my hearers,

its consummation depends

on you,

not on your neighbor but