contributor

XAlexander Orquiza

location

X- Born: USA

- Based: Boston, MA, USA

b. 1980

2014 Essay. Courtesy of the author.

Dec 2011 Interview. Courtesy of Our Own Voice and Rowman & Littlefield.

Our Own Voice December 2011.Amy Besa is a native of the Philippines and with her husband and business partner, Romy Dorotan, also from the Philippines, owns and operates Purple Yam in Ditmas Park, Brooklyn, New York. Previously, the couple owned the Filipino restaurant Cendrillon in New York, which was open from 1995 to 2009.

In 2006, Amy and Romy co-authored Memories of Philippine Kitchens (Stewart, Tabori and Chang, 2006), which won the IACP [interntaional Association of Culinary Professionals] Jane Grigson Award for Distinguished Scholarship in the Quality of Research Presentation.

The book describes the melding of native traditions with those of Chinese, Spanish, and American cuisines. They have spent years tracing the foods of the Philippines, and in the book they share the results of that research. From Lumpia, Pancit, and Kinilaw to Adobo and Lehon (the art of the well-roasted pig), the authors document dishes and culinary techniques that are rapidly disappearing and in some cases unknown to Filipinos whether in the Philippines or abroad.

One year after the catastrophic destruction of Super Typhoon Haiyan, the popular narrative in the news is one of national resiliency. Photos show residents building new neighborhoods in Tacloban named Haiyan that the super typhoon ravaged a year earlier, and stories about the preparations for the visit of Pope Francis in January 2015 are intertwined with recovery from the storm. There is little discussion of the more than six thousand dead or the $2.86 billion in damages. It’s incredibly difficult to find a story about the Philippine government’s own slow deployment of aid or relief in the immediate aftermath of the typhoon.

“Resiliency” is a word one would hope is associated with responding to a natural disaster. But in the case of the media’s coverage of Haiyan, the narrative of resiliency created limited and problematic coverage that created skewed perceptions of the impact of the storm for those on the ground and that allowed Western television journalists to aggrandize themselves before their viewing public.

The primary flaw in the Western media’s coverage of Haiyan was that it relied heavily on the accounts of English speakers. While this may seem a minor detail because the Philippine population is technically bilingual, English proficiency strongly is related to economic class. The English-speaking Filipinos whom Western journalists interviewed thus had higher education levels and salaries than the average citizens from Leyte and Samar, the islands that Haiyan destroyed in one of the poorest regions in the Philippines. One third of the region lives in poverty, the third-highest poverty rate in the country.[1] In Eastern Samar, the area where Haiyan first touched ground, 59.4 percent of the population lives on a per capita earning of less than $224 per year. Leyte and Samar also have some of the lowest education levels in the country. According to the 2008 Philippine National Census, only the chronically underfunded areas of Muslim Mindanao in the Southern Philippines had lower education statistics.[2] One also easily can argue that viewers of the Western news did not grasp the full impact of Haiyan in the images circulated of the typhoon’s destruction because most people in the area do not speak Tagalog, let alone English. Coincidentally, they were also the poor and marginalized in society and thus the most in danger.

What stories did Western journalists miss? One need only look at the nation’s most popular evening news program, TV Patrol and the ABS-CBN network. The Tagalog-speaking massa, or masses, had voiced their frustration over the Philippine government’s lack of preparedness before the typhoon even landed. Even when the typhoon was out at sea, ABS-CBN reporters interviewed residents in Leyte and Samar who were skeptical of the historically inaccurate predictions of PAGASA, the national weather agency in charge of predicting storm paths and weather. Cameramen showed government storm shelters that were hastily constructed of flimsy materials that would come apart during the typhoon, and badly built roads that crumbled under the weight of heavy vehicles. ABS-CBN correctly placed Haiyan within the context of the typhoons that pass regularly through the Philippines. There had already been one tropical depression, seven tropical storms, five severe tropical storms, and six typhoons in the calendar year by the time Haiyan hit in November 2013. Western television reports instead fixated just on Haiyan and failed to contextualize the typhoon within the larger story of storms in the Philippines.

How did Western television news miss out on these voices and stories? More to the point, why did they not have Tagalog-speaking correspondents? Part of the answer lies in the fact that the Southeast Asian bureaus of Western news media are located far away from the Philippines in Jakarta or Singapore. They rely on expatriate freelancers and news stringers for most of their coverage of the Philippines. Moreover, these reporters are based in the capital city of Manila – 356 miles northwest of Leyte-Samar and thus far away from the epicenter of Haiyan’s destruction. The lack of Filipino voices or direct interviews was obvious, especially compared to the Western media’s coverage of the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami in Japan that featured interviews and translations with Japanese speakers from the beginning. One would expect Western news organizations to have hired English-speaking Filipino journalists or Tagalog-speaking global Filipino journalists. But neither were hired.

The second problem was that Western journalists inflated their roles as reporters in the typhoon’s aftermath. I will focus on two examples involving CNN journalists.

First, CNN’s Christiane Amanpour interviewed Philippine President Benigno S. Aquino III on November 12, 2013, and immediately was praised for holding the president responsible with her supposedly hard-hitting questions. She questioned Aquino about his administration’s significantly low casualty estimates compared to the western estimates, as well as the slow deployment of relief four days after the typhoon hit. But Amanpour also framed the last question of the interview in a decidedly American style. “Let me ask you about your responsibility as president,” she said. “Clearly, I don’t know if you agree, but the way you respond, your government responds, to this terrible devastation, will probably define your presidency. What do you say to that?” To be clear, Amanpour was right to ask President Aquino why his government response was so poor. His answers meandered pathetically as he blamed local law enforcement officials for abandoning their posts when the national police failed to support them, and he accused journalists of sensationalism in inflating casualty numbers. But Amanpour framed her questions without the context of Philippine politics. Not only did this question channel the American obsession with political legacies, it ignored the regularity of natural disasters in the Philippines and the fact that most Filipino politicians are remembered most for their stances on corruption and economics. Philippine Inquirer columnist John Nery wrote about Amanpour: “She was asking as an outsider. Even more to the point, she was asking it as an outsider with [George W.] Bush’s Katrina as context.” What is more, the correct question should have been, why wasn’t the national government properly prepared for Haiyan considering how many natural disasters occur in the Philippines?[3] Indeed, Philippine journalists were asking the president and his administration this question in the immediate aftermath of Haiyan. But when Amanpour had the exclusive interview presidential interview with the largest viewership, she failed to ask the most important question about the effects of Haiyan.

Second, CNN’s Anderson Cooper was praised for his on the ground reporting from the city of Tacloban after the typhoon. Like Amanpour, Cooper began reporting on Haiyan five days after the typhoon on November 12. And like Amanpour, he caused a media sensation, this time stating that he did not see “real evidence of organized recovery or relief.” Newspapers, blogs, and media critics praised for him for his visceral style of reporting and his moral outrage over what he perceived as a lack of urgency in the government’s response. He even got into a tiff with ABS-CBN’s prime time news anchor, Korina Sanchez, the wife of Mar Roxas, one of the president’s men in charge of disaster relief. Sanchez was infuriated by Cooper’s critiques of the government and claimed on her morning radio show that Cooper was “mali-mali” (“wrong”) and that he “does not know what he is saying.”[4] But most people backed Cooper. Filipinos even awarded him with a star on the Walk of Fame Philippines.[5] Cooper cried for four days on camera as he interviewed doctors who lacked medical supplies and water, ordinary people who refused to leave the sides of their deceased relatives, and American Marines who grumbled about the Philippine government’s lack of coordination. Cooper repeatedly praised the Filipino people for their “strength and continued courage.” Like Amanpour, he was correct in his actions. But he also was contributing to the default response of national resiliency — the same narrative that Filipino politicians including President Aquino use to sweep the discussion of government preparedness under the rug. Who needs plans when the people themselves could respond even under the direst circumstances? Thus, it was not surprising when the people directly affected by the storm in Leyte and Samar accused the Philippine government of paying more attention to the Western journalists covering the typhoon than the Filipino survivors who were directly affected by it.

While resiliency makes a good story for anniversaries and aftermaths of natural disasters, it sometimes leads to incomplete portrayals of affected peoples and the uncritical analysis of government institutions. The destruction of Typhoon Haiayan in the Philippines was immense. The swift global response in aid and relief was impressive. Those two truths are quite extraordinary. And yet the Western media’s resiliency story of a nation bouncing back from Haiyan obscured two quite ordinary truths of Philippine life: The poor often do not have a voice in the discussion; and foreigners who think they are accurately presenting the Philippines sometimes fail to ask the most obvious questions.

[1] http://www.rappler.com/newsbreak/iq/43341-fact-file-eastern-visayas

[2] http://www.nscb.gov.ph/secstat/d_educ.asp

[3] http://opinion.inquirer.net/71691/the-amanpour-interview-framing-aquino

[4] http://entertainment.inquirer.net/120973/korina-sanchez-reports-from-ormoc-anderson-cooper-still-in-tacloban

[5] https://ph.news.yahoo.com/walk-fame-ph-star-anderson-cooper-rob-schneider-153148712.html

Alfonso Felix Jr., the director of the Historical Conservation Society and publisher of The Poor Man’s Cookbook (1979), realized that the Philippine government was not the place to turn to for a publication that helped the nation’s poor. The presidential administration of Ferdinand Marcos was battling to maintain its power in the face of civil unrest. The country’s economic class divide, long a historical problem, isolated the rich from the struggles of the poor. A cookbook with recipes and instructions for the poor, however useful, was not high on the priority list of the national government, so Felix accepted foreign aid from religious organizations and foreign governments. “We have counted on the kindness and civic spirit of many to make this cookbook and they have not failed,” he wrote in the cookbook’s introduction. But Felix’s reliance on the west revealed that The Poor Man’s Cookbook was more than just a collection of recipes. Indeed, it was a publication that cast the West in a favorable light in the height of the Cold War. The Poor Man’s Cookbook was a tool to win the hearts and minds of the Philippine poor. Its recipes captured frugality and resourcefulness in cooking, and the book’s instructions and diagrams on rice threshing appealed to the masses by efficiently preparing the staple crop of the nation. This piece examines The Poor Man’s Cookbook from two perspectives: as a record of the culinary preferences of the Philippine poor, and as a tool of Cold War western humanitarian aid.

Recipes and content

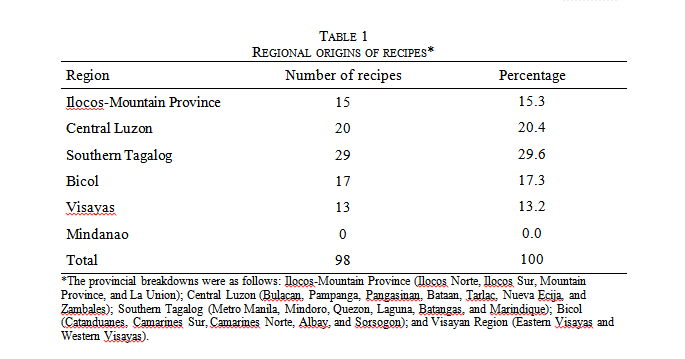

The contents and organization of The Poor Man's Cookbook were fairly standard with the exception of the final section on rice threshers. It was a 100-page soft cover publication that contained glossy color illustrations of each dish printed on stock paper that was portable for use in both home and classroom kitchens. There was a short introduction (6 pages); directions and descriptions of 98 recipes (42 pages); color photographs of each dish (26 pages); a glossary with the names of ingredients in Tagalog, English, and binomial nomenclature (6 pages). The final section on rice hullers with diagrams and descriptions (18 pages) made the cookbook exceptional as it doubled as an instructional manual for simple rice preparation technology for the masses. Readers immediately noticed the authors favored dishes from Luzon just by reading the table of contents. Most of the recipes came from the Central Luzon and Southern Tagalog regions that were close to Manila. The regions of coconut-rich Bicol and bagoong-rich [salted shrimp paste] Northern Luzon constituted nearly a third of the recipes. Recipes from the Visayas region constituted the smallest portion of the cookbook. There were no recipes from Mindanao, a revealing detail of culinary and cultural bias because of the region’s historical battle to create a Muslim independent state that governors in Manila had ignored since the 16th century. While the book’s target audience was poor people throughout the Philippines, it prioritized the flavors of Luzon and maximized the use of ingredients that were readily available in both urban and rural contexts. The eponymous poor man was just as easily a resident of the megalopolis of Manila as he was a poor farmer in the provinces (Table 1).

The dishes received their flavor notes from cheap and plentiful ingredients. Salty tastes came from bagoong, bitter tastes from vinegars and tomatoes, and distinctly Filipino flavors from items such as malunggay [horseradish leaf], garlic, and ginger. Most recipes called for ingredients from the traditional Hispanic soffritto of onion, tomato, and garlic – a legacy of Spanish imperialism originating in the 16th century when Spanish galleons brought New World tomatoes and continental European flavor profiles to the archipelago. 70.4 percent of the recipes used onion, 48.0 percent tomato, and 45.9 percent garlic. Other inexpensive flavoring agents such as ginger (22.4 percent) and malunggay [horseradish leaf] (12.2 percent) provided umami, or savory taste. A few recipes called for bottled ingredients that are ubiquitous around the Philippines. 12.2 percent of the recipes called for coconut vinegar and 11.2 percent for bagoong. A few simple root vegetables, herbs, and cheap bottled ingredients shaped the flavor profile for most of these dishes (Table 2).

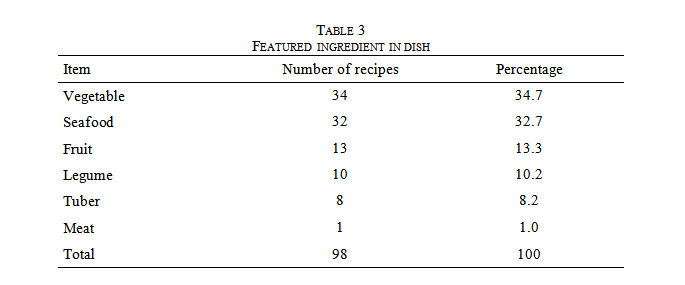

In the same spirit, the primary ingredients in these recipes were also plentiful and cheap. The recipes did not call for expensive proteins such as pork, beef, or chicken. They instead favored cheaper ulam [accompanying dishes] made from produce, legumes, tubers, and seafood that paired well with rice. Two-thirds of the recipes featured vegetables (34.7 percent) or seafood (32.7 percent); the rest used fruits (13.3 percent), legumes (10.2 percent), and tubers (8.2 percent). Only one recipe (dinuguan, or pig’s blood stew) used meat. Two recipes (banana heart burger and meatless lumpia [eggroll] shanghai) substituted meat with banana heart. Unsurprisingly, cheap and plentiful ingredients composed the majority of the poor man’s diet (Table 3).

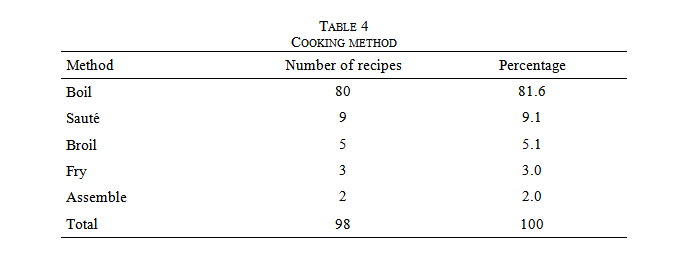

The cooking methods of these recipes used simple preparations. The Philippine tropical heat made long cooking times requiring plenty of fuel impractical, so the cookbook recipes had short cooking times. 81.6 percent of the recipes required little more than boiling ingredients that had been roughly chopped. The rest of the recipes also called for short cooking times: sautéing (9.1 percent), broiling (5.1 percent), deep frying (3.0 percent) and assembling (2.0 percent). The cookbook authors understood that short meals with minimal exposure to heat would appeal to their readership (Table 4).

Finally, the recipes in The Poor Man’s Cookbook maximized nutrients in all ingredients. They even added the water used for rinsing rice to recipes because it contained calcium and thickened soups and stews. 42.6 percent of the recipes called for this “rice washing.” By comparison, 28.6 percent of the recipes used plain water and 17.3 percent used coconut milk (Table 5).

The Poor Man’s Cookbook provided instructions for feeding a family of five Filipinos on a budget of just 1.50 Philippine pesos – or just three US cents a day. These frugal recipes aptly suited the cookbook’s title. But what about the story behind the cookbook’s publication? How did financial support from Western religious societies and governments affect the cookbook?

Publication support and funding

The Philippine government played a minimal role in the contents and creation of The Poor Man’s Cookbook. It paid the salaries of three faculty members who tested seventy cookbook recipes at the Institute of Human Ecology from the University of the Philippines at Los Baños, b. But the chief technician of the Magnolia Dairy Products Division of the San Miguel Corporation also contributed twenty-eight recipes. In the cookbook’s introduction, Alfonso Felix Jr. praised these food scientists for displaying “a very great semi-hidden fund of kindness and civic cooperation,” a trait that he claimed characterized the Filipino people. But in the following sentence, Felix also said the nation’s potential for kindness and civic cooperation lacked “the leadership that we have so far not gotten to bring it to the surface.” Felix thus criticized the Philippine government’s inability to meet the basic needs of the poor. He slyly rebuked the the Philippine government in the seemingly innocuous pages of a cookbook.

Part of the reason why he was able to voice such displeasure with the Philippine government was The Poor Man’s Cookbook was paid for by Western religious and government aid. European and American leaders filled the void for instruction that the Philippine government failed to meet. In the process, they intended to win the hearts and minds of the Philippine masses. It was unsurprising that three Catholic aid organizations helped pay for the cookbook because the Philippine population was 83 percent Catholic in the 1970s. These three religious agencies were Church World Service of Elkhart, Indiana; Catholic Relief Services of Baltimore, Maryland; and MISEREOR of Aachen, Germany. Two American government agencies—The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and The Asia Foundation—paid the majority of the publishing. USAID was the cookbook’s primary sponsor and the organization was founded by President John F. Kennedy in 1961 as the first American government agency committed to foreign aid. Its early Philippine initiatives focused on Muslim populations in Mindanao, but USAID also funded programs for infrastructure, administration, governance, electoral, health, and the environment around the country. The Asia Foundation was the successor to the Committee for Free Asia, a US government organization supported by the National Security Agency and financed by the Central Intelligence Agency; it had also historically backed covert pro-democracy initiatives in Southeast Asia. Finally, the government of Switzerland contributed to the book’s publication via the Swiss Office of Technical Cooperation. A combination of Western religious and government funding made The Poor Man’s Cookbook into an instrument of western goodwill.

The imagined international readership of The Poor Man’s Cookbook hinted at the global intentions of these Western contributors. Felix confidently wrote that the recipes would transfer easily to other “tropical” areas of the world, specifically suggesting Ruanda-Urundi, Peru, and the Sahel. He wanted to hire an illustrator from the College of Fine Arts at the University of the Philippines to draft comics illustrating each dish, its ingredients, a person cooking the recipe, and a simple comic book-style conversation describing the dish’s preparation and nutritional value. In the eyes of the book’s authors and the contributors, The Poor Man’s Cookbook had appeal beyond the Philippines to poor people around the world; perhaps it could also promote Western religious and government ideals in countries besides the Philippines.

The cookbook’s priority to win popular support of the poor was clearest in the contents of the final section on rice hullers. The final 18 pages of book were devoted to diagrams and descriptions of two kinds of rice hullers that would thresh rice, the staple crop of the nation, up to five times more efficiently than traditional methods. Both models required no electricity, were powered by hand, and used just wood, stone, and nails to construct. These hand-operated disc hullers removed the husk, bran, and germ of rice kernels to create “polished” rice. They used less energy than traditional hand-powered mortars and pestles. The book advised readers to place these new hullers in central locations that were part of everyday life such as sari-sari [convenience] stores, rice shops, and in the homes of wealthy provincial families centrally located in the town square. The designers of these rice hullers had clear connections to the promotion of Western religion and government in the Philippines as well. Derek Warburton-Brown prepared the first rice huller design for use in rice stores because it operated best in high volumes. He was formerly a major in the British Royal Corps of Electrical and Mechanical Engineers and a member of the United Nations Industrial Development Organization; Warburton-Brown was the director of the European Chamber of Commerce of the Philippines when the cookbook was published. The second rice huller design was by Willard Unruh, an American Baptist missionary and member of the Mennonite Church. He created a smaller, simpler design tailored for home use that anyone could construct. Unruh had previously served as a missionary in Haiti, Somalia, and Nepal. His work designing a rice huller for the Philippine masses was a natural extension to a career spent as a missionary working to improve food systems and nutrition in the developing world. Thus, all parts of The Poor Man’s Cookbook from the kitchen recipes rice huller diagrams had the imprimatur of the West. Large Western organizations and governments funded its publication for use in kitchens, and individual Western engineers drafted its technical instructions for use in public markets and private homes. They clearly saw food as the key to winning popular support in the Philippines.

Conclusion

With a title like The Poor Man’s Cookbook, a reader automatically knew affordable recipes were inside the book. Dishes logically made use of plentiful, cheap ingredients and maximized their nutritional content. But a close reading of The Poor Man’s Cookbook reveals much more. There was a bias for recipes with origins around Manila. Recipes substituted banana heart for meat, used a handful of ingredients repeatedly, and did not even throw out the water used to wash rice. The story behind the book’s publication showed the importance Western religious organizations and governments placed on providing aid to the Philippine poor. It was not just a cookbook with familiar recipes, but also an instructional manual for preparing the nation’s staple crop in efficient ways. Thus, The Poor Man’s Cookbook was a tool that won over Filipinos with its recipes, keeping stomachs full of rice and political allegiances to the West.

Appendix A

The recipes in The Poor Man’s Cookbook in order are the following:

1. Binagoongan Binnik

2. Calunay (Uray) Salad

3. Cassava (Kamoteng Kahoy) with Vegetables

4. Denengdeng

5. Dinuguan

6. Denengdeng na Saba

7. Daing with Saluyot

8. Ginisang Dried Paayap

9. Inabrao with Dried Dilis

10. Ipon Tamales

11. Inabrao nga Aba

12. Kardis Ginisa

13. Munggo with Talinum

14. Pinakbet

15. Pinalkang

16. Adobong Sapsap

17. Bulanglang

18. Banana Blossom Tortilla

19. Ensaladang Talinum

20. Fish Balls with Misua Soup

21. Guisado

22. Galunggong with Tausi

23. Kinamatisan

24. Kamote Tops with Tausi

25. Mustasa in Misu

26. Malunggay with Bagoong

27. Meatless Burger

28. Meatless Rellenong Talong

29. Papaya at Malunggay

30. Pinais na Alagao

31. Sinigang

32. Susong Bulanglang

33. Suam

34. Tokwa with Tausi

35. Tinolang Tulya

36. Ubod Ng Tubo

37. Burong Mustasa with Egg

38. Bulanglang I

39. Bulanglang II

40. Bola-Bola with Miswa

41. Dilis Sinigang

42. Dilis Escabeche

43. Fish Sinigang

44. Fish and Cabbage Roll

45. Guinataang Laing

46. Inalamangang Kangkong

47. Kalabasang Guisado

48. Kangkong Adobo

49. Laksa

50. Munggo Guisado

51. Munggo Guisado with Dilis

52. Meatless Lumpiang Shanghai

53. Mango Leaves Salad

54. Okoy

55. Okra-Sigarilyas Salad

56. Pechay Guisado

57. Pucherong Galunggong

58. Pinais na Tagunton

59. Sauted Sigarilyas

60. Sayote Patties

61. Squash and Tahong

62. Salted Kamote Tops

63. Salted Fish

64. Sinigang na Puso ng Saging

65. Toge (Sprouted Mongo)

66. Upo Kinamatisan

67. Bagisara

68. Baked Vegetables

69. Cocedo

70. Dulong with Kolis

71. Ginataang Bayabas

72. Ginataang Kuhol

73. Ginataang Kalabasa

74. Ginataang Langka

75. Ginataang Sitao

76. Kulaho

77. Kilawin

78. Kangkong Ginataan

79. Latong

80. Munggo

81. Pickled Dulong or Tabios

82. Pinangat 83. Suso

84. Sarciadong Suso

85. Apan-Apan

86. Banana Heart Burger

87. Ginataan Igi Cag Paayap

88. Ginataan Tambo (Labong) Cag Mais

89. Kinilaw

90. Laswa

91. Laswa II

92. Laswa III

93. Munggo Cag Langka

94. Munggo Cag Alugbati

95. Malunggay Cag Dilis

96. Tinotuan

97. Ubod Cag Munggo

98. Ubod Ginataan

Alex Orquiza’s dissertation, “A Pacific Palate: exchanges in food, nutritional science and cuisine between the United States and the Philippines, 1898-1946,” examines how Filipinos reacted to American food policies. While the actions take place in the Philippines, it is also an American history story analyzing the everyday tangible effects of empire at the periphery. The study explores reforms in schools, advertising, the new English-language popular literature, and the different consumption patterns in Manila and the provinces. Using approaches from anthropology and comparative transnational empire studies, it differs from previous histories of the Philippine-American exchange in its extensive use of Tagalog and Bisaya sources and its goal of analyzing the Filipino middle class alongside the Spanish- and English-speaking ruling elite.

Many of us still look at Spain with nostalgic eyes and claim that we borrowed many foods from THAT colonial power (rellenos, paellas, chorizos, afritadas, etc.). However, if we measured the square footage within business areas in the Philippines devoted to American style fast food chains as opposed to those featuring Spanish foods, you would know who won the food wars in the Philippines.

Alex first came to Cendrillon (our restaurant in SoHo from 1995-2009) around late summer in 2008 following the advice of his dissertation adviser, the eminent anthropologist, Sid Mintz, that he go and see me. Sid became a good friend through other notable academics in NYU and he knew that I had much contact with the most important Philippine food scholar, Doreen Gamboa-Fernandez.

I was personally excited at the thought of knowing someone who was going to devote a good number of years, legwork and brain power doing serious study on the American influence on our food. I had written a short chapter about it in our cookbook, Memories of Philippine Kitchens (Stewart, Tabori and Chang, 2006). My chapter, entitled “The American Influence: Transformations,” albeit brief, expounded on my personal theory on what the Americans did to institutionalize and ingrain a taste preference so thoroughly in the Filipino psyche during this period in Philippine history that we feel the repercussions even more deeply today. Considering that Spain had us under her yoke for 350 years and America only 50, why are we so enamored, bedazzled and bewitched still of all things American especially with its food?

In every type of forum imaginable that deals with Philippine food, no one asks why Filipinos love fried chicken, hamburgers and fries. The one question that is constantly asked by both Filipinos and non-Filipinos alike: Why is our food not mainstream in the US and for that matter, wherever Filipinos have settled? The question does not even ask why our love for American food is not in the least bit reciprocated. Filipinos themselves are oblivious of their taste preference. I guess it reflects upon how this worldview accepts American food as a default—that it is loved and eaten everywhere, it is a universal food and no one even questions why we eat it all the time.

But life has its many surprises. Alex’s findings give us big, bold clues as to why Filipino food remained in the shadows too long compared with the growing Filipino population in the US. The Americans wanted it that way for they saw no redeeming value to it. And in my opinion, it is because of gross ignorance on their part and a desire to make the Philippines a receptive market to their products and goods NOT that there is something inherently inferior in our food.

Alex and I conducted an email exchange of ideas and questions triggered by his research findings not only in the libraries but also out in the marketplace both in the US and the home country and how our food is presented and viewed by both Filipinos and non-Filipinos alike.

AMY BESA: Alex, can you briefly describe what your research is about?

ALEX ORQUIZA: I'm a first-generation Filipino-American from the San Francisco Bay Area now finishing my PhD in the Johns Hopkins department of history. For the better part of the last three years, I've been researching the changes and American influences on Filipino cuisine during the American Period. I came to this project because I've always been interested in the intersection of food and history. I had originally intended to do a dissertation about the disproportionate representation of Southeast Asian restaurants in the US. There are a ton of Filipinos in the country, yet there are few Filipino restaurants. Alternatively, there are almost no Thais, but you can find Thai restaurants everywhere. But as an historian, I sought the answers in the past and am convinced that the colonial legacy of the Americans in the Philippines still resonates today in Filipino food.

Amy: Tell me more about your approach or mindset when you decided you were going to pin down every source available in both the US and in the Philippines that would be relevant to the Philippine-American food exchange from 1898—1946.

Alex: My weird 18th-century approach to the project, with the "rigor and discipline" you cite, really comes from two places. First, I'm an historian by training and appreciate work that can be supported with evidence. There are not many cultural historians working on the Philippine-American exchange in the first place, and because of the destruction of the archives in Manila during World War II, very few works that cite archives and original resources. The only way to write this story is to chase down every little bit of minutiae—menus, advertisements, school syllabuses, diary accounts, and letters—that I could find.

Secondly, I recognized that so much of the historical research on the American Period in the Philippines was focused solely on Manila. Perhaps it's a function of the fact that much of the scholarship, and many of the scholars, is based in the National Capital Region. But Manila is not representative of the rest of the provinces. I wanted to find these regional stories, compare them against each other, and find explanations for the differences in the food histories of Luzon, Visayas and Mindanao during the 20th century.

Before I left for the Philippines, I spent six months researching in New York, Chicago, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Chicago and Washington DC for American records on food. Not surprisingly, most of the accounts written by Americans described a distaste and little interest in trying Filipino food. There were, however, some exceptions with Americans impressed by fiestas, the variety of produce, and a real fascination with lechon.

So when I arrived in the Philippines, I was very excited to see that Filipinos oftentimes reacted the same way to American food. It took a whole lot of advertising, educating, and instruction to convince Filipinos to eat like Americans—and it wasn't always successful. So I just went in with an open mind, realized I needed to spend double the amount of time I had intended in the archives, and ended up seeing the country through its university and provincial government libraries.

AMY: I always describe you to others as someone who is both an insider and an outsider to Philippine society having been born and raised in California, but choosing to focus on Philippine foodways for your dissertation. Can you expand on that? Where are you most at home, here in the US or in the Philippines?

ALEX: I really believe that the reason why I was successful in finding so many sources was because of my status as a Fil-Am. As you said, I am "an insider and an outsider to the Philippine culture." My dad is Nuevo Ecijeño and my mom is Ilocano, so right off the bat, I instinctively wanted to conduct research outside of Manila. I quickly enrolled in intensive Tagalog instruction when I arrived and over the course of my research, was happily speaking Tagalog with colleagues and librarians who immediately respected me as an American-trained Fil-Am interested in immersing myself in non-American viewpoints on Philippine history. I grew up surrounded by titos and titas in one of the most densely Filipino communities in the United States. But that is not the same thing as the Philippines. After two years, I definitely have my moments when I will tell my Fil-Am friends that the differences are just more than we realize. Being a Fil-Am really prepares one just a small fraction for the Philippines.

That being said, I feel equally at home in both countries. My mom and dad live in California. But I have so many relatives in Manila that holidays there are actually more exciting than here. I love that new friends are so easily made in the Philippines and take our reputation for hospitality very much to heart in the States. I definitely want to return and teach again at U[niversity of the] P[hilippines] Diliman in the future. I recognize that my career as an American scholar affords me more fellowship opportunities than my colleagues in the Philippines. I've only been able to do this thanks to funding from Johns Hopkins and the Fulbright Commission. When I see how much my colleagues in the Philippines believe in my project, I truly feel indebted to all those who helped me there. It would be foolish to stay in the US and not to give back.

AMY: What do you think is the mindset of restaurateurs in Manila that feature Filipino food? I think what they produce in their restaurants would be a Rorschach test on how they feel about Filipino food.

I ask this question because you discovered through your research how the Americans who were in the Philippines during the colonial period showed nothing but disgust for the Filipino food they encountered. I somehow feel that the legacy of having our food so disparaged and dismissed easily lingers on to this day.

I am still asked WHY Filipino food is not mainstream in the US. For most people, mainstream means that it should be as ubiquitous as the Thai and Vietnamese restaurants that litter the landscape. I always respond that we should NOT compare ourselves to these other cuisines and how they have proliferated in many cities. This feeling is so ingrained that I am convinced that people like to wallow in their misery. And when we break through this glass ceiling, they are so blinded by this “victimhood” that they can't see the great strides we have made in moving our food forward in this country.

ALEX: My restaurant view of Manila is admittedly small because, as a grad student on stipend, I was penny-pinching and did not break my bank at the “sosyal na sosyal” places. So I spent the majority of my money eating at “turo turos,” to be honest. But I'll give you a few vignettes instead to let you know how much I'd rather be eating kinilaw in Dumaguete or lechon in Cebu.

I was dragged unwillingly to Abé in Fort Bonifacio one night by a bunch of Americans on a Saturday night. I wanted to take everyone to the Pasig dampa but was outnumbered because my American dining companions were told that Abé was "the place" to go for Filipino food, which was shocking to me because, while I respect what they're doing at that restaurant by cleaning up presentation and it's a beautiful space, it's pretty far removed from how many Filipinos eat. Anyway, while we were there, my American companions unfortunately voiced their views of Filipino food as "something overcooked with rice" or "pork with pork." As the only ethnic Filipino there, I certainly was upset and spent most of the evening talking to the waiters in Tagalog about how disappointed I was in dining with such closed-minded people.

Luckily, most Americans are not this bad and many of the Americans I dined with in Manila would rather go to the Cubao dampa than Abé. But there are a few places that I got excited about while I was there. Reyes Barbecue, which is a chain, made a remarkably good inihaw na pusit. Within UP, Chocolate Kiss served a pretty great sinigang. Binalot tries to follow along the ethos of baon packed individually in a banana leaf. For someone who didn't want to spend more than P250 per meal, I was a very happy camper with the amount of dining options.

But it's that high price point that worries me. The overwhelming majority of higher-priced restaurants in the Pinas are still not serving Filipino food. The pride and drive to create, say, a Danny Meyer empire of making really well-made, well-marketed Filipino food still hasn't hit the industry in Manila. Most Filipinos are still satisfied to equate the best meals with buffets in hotels in Makati. An intimate, local, and proud restaurant that we could recommend to our expat friends visiting Manila still escapes me. Which is why I still tell my friends to just go to the dampa.

AMY: Finally, do you think your research can contribute towards dealing with this mindset and provide a “satisfying” explanation to the aggrieved Filipino regarding this perceived slight by the American diner to our food?

ALEX: I think my research could help explain why this colonial mindset still exists for sure. I don't think I realized it was so pervasive when I was growing up in California because, to be honest, I grew up surrounded by it. Most of the older Fil-Ams I knew were so interested in showing they had made it in the US that looking back to the Philippines was a low priority. I didn't know a whole lot when I first arrived in the Philippines myself just because it's not something we first-generations had much experience with, no matter how many summers we flew back to visit our families. I know things have changed and there's a larger number of balikbayan who spent more time in the Pinas than kids born in the US like me. But even then, the knowledge of what the Americans did in the Philippines is under explored in American academia. In the Philippines, it is looked at critically and receives a proper post-colonial critique. However, not enough of that story is taught to Fil-Ams and if they are exposed to it, it's at the university level in the few Filipino American history courses in the country when it should be a large part of the American history survey or curriculum. I'd put it this way: the British education system spends a lot more time talking about their legacy in India, the Caribbean and Africa than we do. While it was only 50 years, the American Period in the Philippines still has incredibly resonant repercussions simply because, well, the reach of the US is still so strong in the Philippines. That may be a controversial viewpoint for many, but it's undeniable.

ALEX: My turn to ask you questions: Why are some restaurateurs still obsessed with this idea of bringing Filipino cuisine to the mainstream?

(Note: At this point, I did not get the chance to answer Alex’s questions via email, but I will answer them here.)

AMY: Food is so much intertwined with identity and self-respect. This is why I feel so many Filipinos want a “restaurant they can be proud of, something to showcase their food and culture” because if you accept their food, you accept them, too, in the social context of the US. The problem is that, just like adobo and its limitless variations, everyone has his or her own idea of what that place should be. So the quest goes on because many Filipinos believe that they are the only ones who know what a true Filipino restaurant should be. It is good that such pride exists and a demand for a good Filipino restaurant is bottomless. But the downside to this is the “crab mentality” and knives are ever ready to stick it into anyone who deigns puts his or her stamp on the food that does not match their own.

ALEX: What are the disadvantages of mainstreaming Filipino cuisine so that it's as ubiquitous like Thai or Vietnamese?

AMY: You know the saying “beware of answered prayers.” Everyone wants to see a proliferation of Filipino restaurants around just like Thai and Vietnamese restaurants which sprout all over the place ad nauseum. When you talk to people whose food has been mainstreamed like the Chinese and Indians about how their food is represented in these restaurants, they always say that the food is no good and does not compare to home cooking. The restaurant industry has really suffered a huge decline in the past couple of decades and it is caused by twin factors of people demanding good food for cheap prices and soaring prices of food, gasoline, kitchen supplies everywhere. Most businesses are forced to use shortcuts (packaged mixes, cheap cuts of meat, frozen fish), hire inexperienced cheap labor and cut costs wherever they can. If people want to have many good Filipino restaurants around, they should put their money where their mouth is: they should be willing to pay the price of what it takes to build one and keep it going.

ALEX: Do Filipinos in the US play an active role in introducing Filipino cuisine to other Americans?

AMY: Of course, they do and the more enlightened they are about our history and how our lives are affected on a daily basis by what happened a century ago, the better we will be for it. One cannot define a good strategy in promoting our food in this country without that understanding. Where do you start? You can see the results of people who try based on assumptions that are all over the map. The worst is the assumption that our food is brown, oily and stinky and so we must surreptitiously pass it on to the unsuspecting American just in case they might like it and then we tell them it is Filipino if they like it. I get horrified when I see posts like this on Facebook.

Sometimes it is good to have a discussion about this with people who have no emotional stake in the subject matter. It happened earlier this year when I had a meeting with Leslie Stoker, the President of my publisher, Stewart, Tabori and Chang. She was quite excited that the head of the London-based Sales Department of their holding company had specifically picked out Memories for a revised and updated edition because of its sales potential. In this day and age, the publishing world is no longer run by its editorial board, but rather it sales department. So if Sales says this book is a seller, we need to have it updated to reflect the new restaurant, Purple Yam (the first edition ended with a chapter on Cendrillon recipes), then it will have a much longer life in print. Sales had deemed it to be THE Philippine cookbook that people go to and wanted to take the opportunity to increase its sales all over the world.

---

At that moment, I felt some pride in what we had accomplished. To stoke the fire, I said, “Yes, this would be good for Filipinos because they feel that their food is largely ignored here and abroad.” Before I could add to that, Leslie looked at me and said, "Well, it is because we do not know enough about it. That’s why we need this book to solve that problem.”

Well, that pretty much shut me up. How simple! Our food is not mainstream because people do not know about it and we need more books like Memories to educate people about it. So much for the hand wringing and gnashing of teeth.

I really had a good laugh after that. And I proceeded to rid my mind with all that baggage. This is really what we should all do in the new year of 2012. Throw out all the baggage and start with a fresh look because our food is good. People will love it when they learn about it. We wish all of you a year of happy and healthy eating. And eat that Pinoy food with love and relish it because there is nothing like it in the world.

comments

X